I grew up in the USA in the 60’s, when dancing was transitioning from dancing with a partner in a room full of partners

to dancing individually in a room full of individuals.

We were ‘doing our own thing’, breaking from ‘tradition’, which we figured went back to the beginnings of time. My Western European background had no memories of any way to dance socially, other than with a partner. Even square dancing needed a partner.

When I discovered Balkan folk dancing, part of its appeal was the novelty of dancing non-partner in a connected line – a completely different ‘tradition’. I wondered – how could two such different traditions evolve parallel to each other on the same continent?

As usual, I was asking the wrong question. I came to understand that, instead of evolving in two directions over the same time period, North and West Europe evolved in a direction unique to itself, while Southeast Europe, and indeed most of the rest of the world, remained dancing in time-honored ways.

The way people dance, and the way they organize themselves while dancing, is a reflection of the way they organize their society in general; of their social priorities. The first priority of a human is survival – living until the next day, the next season, a natural death in old age. The second priority is the survival of your genes – your family. Family can be defined in many ways. Today we tend to think of a simple nuclear family – mother, father, children. A couple of generations ago it included grandparents, aunts & uncles, cousins. Many cultures include godparents, adopted children, clan members – the list varies greatly.

An important criteria for what constitutes a family is how many people it takes to provide a sustainable lifestyle for all. In today’s monetized society, where every effort has a monetary value, a one- or two-parent family is expected to provide for themselves and their children, with tax-funded assistance from the state. In pre-monetary, pre-state cultures, human labour and the ease of growing/gathering food were the determiners. The family needed to be large enough so that pooled efforts created a surplus – to allow for some slack – extra food or shelter so someone could be sick or old, or a young child, or heavily pregnant – without jeapordising the survival of the group. Then there are the issues of self-defense and inbreeding. One needs a number of people to defend the group from attacks, and to ensure a healthy gene pool. On the other hand, too many people means food sources and natural resources are unsustainably depleted, communication and co-operation become difficult.

However the family is defined, it is of extreme importance in most cultures. Family not only brings one into this world, it defines one’s place in it. For most people one’s family is one’s identity. This is a fact little appreciated by us Westerners, with our mass media and well-developed social institutions, who have among the weakest family ties in the world. For most of human history, people were raised outside of cities or countries that had a direct impact on their life. There were no written laws that were consistently enforced, no police or military that protected one, no written language, books, schools or mass media to shape one’s thinking, no knowledge of jobs or careers one could aspire to, no counselors to offer guidance, no one out there you could trust or even understand. All of these functions were filled by your family. Even today, in many parts of the world where governments are poor, weak, or corrupt, family is your first and most reliable teacher, provider, and protector. The family is the womb, and without it you are naked, a stranger in a strange land. There is no other social safety net.

The family was ruled by the patriarch – usually but not always the oldest male. In a culture without written language, knowledge had to be accumulated by personal experience, so age was more correlated to wisdom. The patriarch was responsible for the well-being of the entire family. The success of the family was often due to the most efficient use of each person’s skills, so the patriarch was both foreman and personnel manager. He had to make the tough decisions, based on personal experience, as to whose desires had to be subverted for the good of the whole. Often they were the desires of the young and inexperienced. The young, on the other hand, had to take as a given that their lack of experience disqualified them from having equal weight in decision-making. In a stable rural society with no available knowledge of life beyond its borders, this system was by and large sound.

In an economy largely without money, and with barely enough land to survive on, one of the very few ways a family could change its fortunes was by a judicious marriage – an alliance of resources with another equally or more wealthy family. It was the patriarch’s solemn responsibility to the entire family to make the right choice. The welfare of the family depended on it. A marriage to a poorer family could affect family fortunes for generations. Marriage-age children could not be trusted to choose partners wisely. At least that’s the way it worked in theory. Certainly parents wanted their children to be happy, and if the young fancied partners from families of similar social status, parents might not object. Parental approval was always important, however, so adult limitation of the opportunities for young people to be together was nearly universal. Hence dance was organized to limit young people’s ability to be alone with the opposite sex unless under adult supervision.

Whether they are hunter-gatherers or nomads or simple farmers, people all over the planet have traditionally organized themselves into cohesive, rather small, but not too small groups – a few families, a village, a tribe or clan. Usually, people in that group worked together in sub-units – the men hunted or worked flocks or fields together, the women processed food or wove fabric or tended children together, a family gathered to eat and sleep, young (or old) men gathered with young (or old) women to select mates (or mates for their children). Periodically the entire group would gather to reaffirm the bonds that united them, and that reaffirmation almost always included singing and dancing together.

There are, of course, other reasons to dance. Healing medicine dances, storytelling dances, dances mimicking animals or work patterns, funny dances, religious dances, dances invoking rain or a good harvest or hunt – special reasons require special dances, usually led by specialists. Not everyone joins in these dances – it would be considered unthinkable, or maybe it’s forbidden. Further, in many cultures there is no distinction between sacred and secular. A festival dance is also a healing dance is also an invocation to a greater power. However it’s still true that an ‘everybody dance’ is an important, possibly critical component of a culture, and the people in the culture. The ‘everybody dance’ is a physical embodiment of ‘us’. Everyone else is ‘them’.

And so it has been over most of the planet over most of time. Relatively small groups gather to cement their bonds by chanting, singing, making music, and dancing together. Because they are a village, or a tribe, they dance as a village or tribe. The all-inclusive nature of the dance is what signifies and strengthens the unity of the group. It is a visceral thing. Holding hands or locking arms, stamping feet or clapping hands, singing or bouncing together, moving together to the same beat, puts everyone on the same wavelength, heartbeats start synching. We are a social species and our psyches and bodies need visual, auditory and physical manifestations of inclusion.

Dancing in groups, doing the same movements in unison to the same rhythm – that’s the way we humans have bonded when we gather together. When we weren’t dancing as a tribal or village whole, we traditionally danced as men (hunters), or women (bringers of fertility), or some specialty group – almost any configuration except a male-female couple. Until recently, it appears, Western and Northern Europe was no different.

I am indebted to a scholar of social dance, Nancy Walker, of Danza Antiqua, Mercersburg, PA.danzaantiqua@embarqmail.com. She graciously consented to review the following depictions of dance for historical accuracy, thus saving me from many blunders. However, the opinions expressed about the social significance of these depictions are entirely my own.

Courtly Love – the West Breaks Free

So how come Western and Northern Europe started doing things differently from the rest of the world? What broke our affinity for family/tribal dancing, transforming it into couple dancing? It started innocently enough, as an entertainment among noble castle dwellers in southern France around 1100 AD. Life was pretty good for these people – they were rich, secure, and had lots of free time. However, people in these courts were subject to the same rules around marriage as most everyone else in the world – marriage was an arrangement between families for their mutual benefit, and for the purposes of continuing bloodlines – the preferences of the potential spouses were of little concern.

The husbands had to do knightly deeds occasionally, which meant long spells away from their wives, who were confined to the castle. The wives consoled themselves by listening to poetry and songs of traveling minstrels. The minstrels, in turn, began crafting a literature suited to their clients – a literature in which the strict bonds of marriage could be superceded, at least in the imagination, by another code of conduct, called by some “courtly love”. Quoting Wikipedia “In essence, courtly love was an experience between erotic desire and spiritual attainment, “a love at once illicit and morally elevating, passionate and disciplined, humiliating and exalting, human and transcendent“.[4].” For more on courtly love, see this link. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Courtly_love

Famed scholar of human beliefs Joseph Campbell claims the Troubadors’ invention of courtly or romantic love is one of the West’s greatest contributions to world civilization.

Scholars are still debating just how much courtly love was literary fantasy and how much was romance (or lust) practiced in real life. What is certain is that the idea of courtly love (sometimes called The Game of Love) quickly spread around the courts of Western Europe. What made courtly love exciting was that the choice of lover had to be someone other than your spouse. It legitimized the idea that it was acceptable, even desirable, to have a relationship outside of the family with someone of the opposite sex, based on attraction and/or sentiment. Previously, in almost all cultures worldwide, having such a relationship in public was considered a threat to the stability of marriage, and thus family alliances, and thus the stability of the institutions of family, village, tribe, or religion. What made Courtly Love revolutionary was its conception as the ultimate moral authority, transcending all others. Only the rich and powerful could afford to indulge in such behaviour.

Political and Social Transformation

Meanwhile in Europe, other historical trends were beginning to separate West and North from Southeast. Until the Renaissance began in the 1400’s, rulers everywhere held both religious and secular powers. Kings may bridle at Church decrees, but a king’s legitimacy was on shaky ground unless he was crowned by a pope. Thus popes could pressure kings to enforce religious doctrine.

In Southeastern Europe the Byzantine emperor was the head of both church and state. Church officials were in effect state employees, but because they were ‘in house’, they had a seat at the table of decision-making. When Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453, a similar Islamic system replaced it, and little changed in that part of the world until the Ottoman Empire’s collapse in 1918. The age-old pattern of dancing communally, as a village or a tribe, continued until the Communist takeovers of the 1940’s.

However in Europe’s North and West, secular rulers were gaining power at the expense of the Church. Henry the Eighth separated the English from the Roman Catholic church, and several German princes did the same. Moral authority was now subject to Church vs State feuds, and the State often had the upper hand.

Whereas religion usually considered economic innovation as not supported by scripture and a distraction from otherworldly goals, the state usually favored innovation, as it brought in new revenues, making the state more powerful in its competition with the church and other states. The charging of interest on borrowed money was no longer outlawed and banks became more powerful. Commerce was encouraged, even if it hurt local craftsmen and farmers.

Intellectual innovation was also encouraged more by the state than the church, as it went hand in hand with scientific and economic innovation. By the late 1700’s freethinkers were challenging all authority, declaring such radical ideas as a universe run by ‘natural law’ rather than by the will of God, and the universal right of individuals to control their own destiny and have a say in how they’re governed. The flip side of government support of intellectual freedom, was that rulers could no longer claim to rule by ‘divine right’. They had to justify their claim to power by purporting to consult with the governed.

As commercial interests became more powerful, they became supporters of governments, who began to favor commercial interests over the landed gentry. By the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution in the early 1800’s, countrysides were being devastated by resource extraction, factories, and slum cities built to house workers forced off the land.

Dance Transformed

What’s all this have to do with dancing in couples? Everything. Dancing in couples would have remained a pastime exclusive to royal courts had the profound social upheavals mentioned above not occurred at the same time.

- Weakening of the power of the Church encouraged people to think more in terms of self-fulfillment than self-sacrifice.

- Consolidation of power by the state, development and enforcement of the rule of law, printing books, newspapers, opening schools, disseminating new ideas – all contributed to the decline of the authority of the family patriarch. Schools and media began to replace family members as sources of knowledge. State-trained teachers often clashed (and still do) with parents for control of influence over children’s education.

- The spread of intellectual concepts such as the right of a person to control his/her own destiny emboldened youth, while weakening the power of family patriarchs.

- The rise of commerce fueled the rise of a middle class. The middle class wanted to emulate the nobility, so they began dancing in couples. The upper classes grumbled, but could not prevent it.

- The increasing power of the middle class, and concurrent weakening of the nobility, meant the two began mixing socially. Couple dancing, with its ‘change partner’ feature, facilitated mixing of previously unmixable social groups.

- Such mixing provided opportunities for young people to meet and develop bonds outside of the control of family patriarchs.

- The lure of living a life of romance, away from extended family ties and strictures, worked to the benefit of capitalists, who needed to pull labourers away from family farms and into their factories. Driving people off agricultural land, leaving them little choice but to move to cities to work in factories, broke up extended families into more portable units, and weakened ties to peripheral family members.

- Smaller families were more easily uprooted families, which also suited the needs of manufacturers, who wanted to locate their factories near resources or markets – not necessarily pleasant working conditions. The state was left to provide the social safety net previously provided by extended family, which further weakened the family while extending the influence of the state.

- As the middle class grew, so did its contact with lower classes, who also began dancing in couples, because their weakened patriarchs and family ties could no longer control their young.

Meanwhile, Southeast Europe slumbered in its Midieval tribal consciousness.

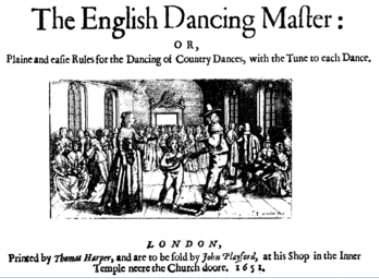

Playford

Many of these social upheavals happened first in England, and in 1651 a book was published that is indicative of a culture in transition. Court dances were becoming popular ways for the upwardly mobile to mingle with the old guard, and for the lower classes to emulate the upper, but first you had to know how to do the dances, or you were kicked off the dance floor. Dances had complex patterns, which were learned by the nobility from Dancing Masters – courtiers supported by the nobility as private tutors. Access to these Dancing Masters was difficult and expensive for the upwardly mobile lower classes.

First titled The Dancing Master, (later The English Dancing Master, various editions of the book remained in print for 75 years), John Playford’s book of instructions for 105 popular dances democratized dancing by making its accomplishment possible for the masses. With Playford’s books, more people could not only dance, they were tacitly granted authority to teach others. In addition, the books also published the melodies for each dance, so even humble fiddlers could accompany humble dancers. To this day Playford’s books are the cornerstone of English country dance. As the book was easily transported, it helped spread English-style dancing to Continental Europe, where it influenced folk dancing in many countries.

Another change

Country dances with formations similar to Playford’s were still popular in Jane Austen’s England (early 1800’s), but soon the forces of social change were to coalesce to create a dramatic shift in dance form. Though Playford’s book brought English couple dancing to the masses, people were still dancing in ‘villages’ – sets of couples dancing publicly together, touching only briefly, and visible for supervision to all. Meanwhile, another dance form was becoming popular in Central Europe.

We have no idea who the first people were who danced man-facing-woman, holding each other close. Wikipedia says “Men and women dancing as couples, both holding one hand of their partner, and “embracing” each other, can be seen in illustrations from 15th-century Germany.[1] …..Danse de Paysans’ (Peasant’s Dance) by Théodore de Bry (1528–1598) shows a couple with a man lifting his partner off the ground, and the man pulling the woman towards him while holding her closely with both arms. His Danse de Seigneurs et Dames (Dance of the Lords and Ladies) features one Lord with his arms around the waist of his Lady.[3] …..An old couple dance which can be found all over Northern Europe is known as “Manchester” or “Lott is Dead”. In Bavaria words to the music include “One, two, three and one is four, Dianderl lifts up her skirt And shows me her knees”, and in Bavaria one verse invites the girl to leave her bedroom window open to allow a visit from her partner.[5] “

Many other couple dances were popular in folk cultures

We do know that the first face-to-face-embrace style couple dance to become popular Europe-wide was the Waltz. Nancy from Danza Antigua cites research by Elizabeth Aldrich, who “included this wonderful information in her book “From the Ballroom to Hell“, Northwestern Univ. Press, 1991. The waltz was first mentioned as “valse” in 1778 to name a figure within a group dance in several French contredanses : (Dauternaux, Receuil d’Airs de Contre-Danses. Paris, 1778). The waltz was known to have been popular in New Orleans within the first few years of the 19th century, but in all the ballrooms in Europe & the rest of the U.S., it continued to be used solely as a figure in country dances & cotillions. We are really not certain the exact year the waltz broke away from these group dances & became a social round dance on its own right, but we do know that one of the first dance manuals to thoroughly describe the waltz as a couple dance was by the London Dancing master, Thomas Wilson who wrote ” A Description of the Correct Method of Waltzing, the Truly Fashionable Species of Dancing” in 1816.”

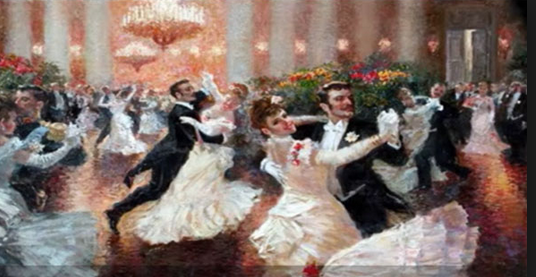

Those dizzying spins were thought by some to spell the end of civilization. What upset the keepers of moral purity was not only the lascivious nature of the dancers’ positions, but also the fact that they were in their own private world, backs turned to others, cut off from easy observation. The ‘village’ had disappeared. The family was reduced to two people.

Another face-to-face-embrace style couple dance to become popular Europe-wide started in Bohemia in the 1830’s, although it did not burst forth into society ballrooms until the year 1844. It was called the Polka. It became so popular that 1844 became known as the Year of Polkamania.

Social dance authority Richard Powers, in his website, says “The Polka’s good-natured quality of wholesome joy finally made closed-couple turning acceptable, introducing thousands of dancers to the pleasure of spinning in the arms of another. Once they tasted this euphoria, dancers quickly developed an appetite for more.” Richard Powers has lots more information; see http://socialdance.stanford.edu/syllabi/dance_histories.htm

The floodgates were opened and they have been open since. Couple dances soon replaced group dances, despite condemnation from all possible authorities, precisely because the social revolutions of the previous 500 years rendered those authorities impotent. Enough single young people had attained enough independence and confidence to be able to make their own choices, and they chose dances that stimulated the body as well as the brain.

The Final Blow

In the 20th century, new methods of social influence came to dominate society – advertising and mass media. The aspirations of adults became shaped by the dangling of tempting goods promoted as saving labour, indulging comfort, enhancing beauty, and increasing social status. Children also became targets, creating for them a sense that the universe of products aimed at them was more interesting and appealing than interaction with their parents and siblings. The final blow to communal dancing came with my generation, whose social cues were taken mostly from impersonal media sources – movies, TV, radio, fanzines. Self indulgence was so ingrained in us that many of us could not relate to learning the communication skills required to dance close to another. Bouncing to an inner rhythm was sufficient. ‘Us’ and ‘them’ became ‘me’ and ‘everyone else’.

What’s next?

The shrinking of social groupings, from tribe to extended family to nuclear family to solo individual has been hailed as a triumph – total personal control over one’s life without constraints from others (within the bounds of state-defined law). However the flip side of freedom from social restraint is isolation. Record numbers of people in our culture suffer from lack of physical contact with another human. Loneliness, neuroticism, depression, and suicide are rampant. Corporate-sponsored entertainment is proving insufficient to replace the reassurances provided by people touching and singing, making music, and moving in sync with other people. We may think we’ve evolved away from tribalism, we may view tribalism, especially political tribalism, as a threat, and it can be.

However, tribalism in the sensual, physical sense, is wired into us. We need communal movement, connecting with our hearts, minds and bodies simultaneously. It’s the most multifaceted, intense way to feel alive, in the moment, and at one with each other. Ironically, the cultures some consider the most ‘primitive’ in Europe, and the most ‘tribal’ as well, the Balkan countries, are the best reservoirs of tribal dance, in a manner closest to our nearly universal human roots.

As our species contemplates its own demise, as a seemingly unstoppable trajectory of social disintegration hurtles us ever further into the unknown, it’s reassuring to know a time-tested pattern of social bonding exists among us, on our doorstep.