2nd Phase: 1930’s – 1950’s:

Summary of Phase 1 [the Top-Down Phase]: 1880’s -1930’s

What are ‘we’ going to do about ‘them’ in our midst? Making ‘them’ more like ‘us’.

Various liberal-minded social workers, educators, physical education enthusiasts, and dance instructors – all trying to establish new fields of expertise in a new country busy inventing itself – coalesced around the idea that ‘folk dancing’ was good for whatever they thought needed improving. Some were moralists, believing the ‘old’ ways were superior to the newfangled, some wanted to blend and harmonize disparate cultures, some wanted an easy, fun way to get people moving, some saw a business opportunity; many were a combination of these inclinations. What all of these people had in common was a desire to adapt elements of a relatively static, self-contained, rural culture’s social expressions to the perceived needs of an increasingly dynamic urban culture.

As Marjana Laušević, author of Balkan Fascination [Oxford University Press, 2007] writes: “Interestingly, this sentiment is prevalent in the Balkan scene nearly a century later. What Tomko (1999: 213) says for Hinman and Burchenal is just as applicable today to many participants in the Balkan music and dance scene. They “keenly felt the absence of comparable traditions and roots for modern America, and creatively tried to fashion a past from other (European) traditions. This fashioning was in every way re-constitutive; it selected, arranged, and appropriated for its own ends rather than attempting to re-install European originals.”

Dances, costumes, music were means to an end, and the end was not an understanding of the source culture, but rather the creation of a new stew where no ingredient dominated: a blending of cultures where each was equally interesting and valid, activity without resorting to sordid ‘commercial’ pleasures (like jazz!), exercise without hard work, ‘wholesome’ socialization for the young.

By the 1930’s, the efforts of these and many other pioneers were firmly established in schools, settlement houses, urban recreation centers, and dance academies. The intellectual framework and top-down leadership was in place, and many people had a rudimentary, often 3rd-hand knowledge of folk dance principles, steps, and their execution. What was missing was an enthusiastic response from the general population. Folk dance was a ‘should do’, not ‘the bees knees’.

2nd Phase: 1930’s – 1950’s;

From the Bottom Up – Immigrants Re-invent the Scene.

‘They’ (in our midst) are like ‘us’ and help ‘us’ have fun.

I am indebted to Bosnian-American author Marjana Laušević, whose book Balkan Fascination [Oxford University Press, 2007] is the foundation of the historical references in this post. I have borrowed extensively from her writings. Excerpts from Laušević’s book are in italics. However, it should be assumed that opinions expressed regarding developments outlined here are not those of Laušević, but those arising from my personal experience.

This post chronicles what I (and Laušević) considers the 2nd phase in the development of what we now call recreational or international folk dancing. In each phase ‘we’, the settled Americans driving the phase, had a different idea of who ‘they’, the ‘folk’ were. For let’s be clear – folk dancing is not, among recreational folk dancers anyway, dancing BY the ‘folk’, it’s US dancing our imagined IDEA of the ‘folk’. It’s one culture selectively imagining another for its own purposes. What those purposes are helps define what we imagine the ‘folk’ to be, and how we conceptualize and dance ‘their’ dances.

“Mary Wood Hinman [see ‘The Pioneers” 1st Phase, DB], then active in New York, attributed changes she observed as folk dancing developed to changes in American society at large…What Hinman was implying was a shift from bodily exercize to the creation of fun, from folk dancing as a drill, a means of achieving physical vigor, to dancing as an engaging physical activity. In its then new incarnation, folk dancing was used not to discipline, not to shape the bodies and educate the foreign and the poor, but to entertain, to enable and to teach people to have fun, interact with each other, and develop interests in others. Here, the agency is in the hands of the participants. Hinman concluded that any existing resentment toward the folk dance programs in school curricula was to be blamed on the fact that the fun of mutual interaction between the sexes had been robbed from folk dancing when the dances were introduced separately to girls and boys…The trend shifted away from viewing people as bodies to be acted upon toward an emphasis on the interactive and expressive experience of individuals...

From Training to Entertaining

“…While in the first period folk dancing was used to promote tolerance among various American immigrant groups, in the second period it was also seen as an activity that symbolically promoted peace among the peoples of the world… A new type of international awareness arose in the United States during World War I….folk dances and songs were used as the best representatives of different nations, rather than different immigrant groups. The earlier narrow national perspective was broadened, and along with the idea of various immigrant groups comprising the American nation, the united American nation was celebrated for its leadership of the other nations of the world...”

“Henry Glass, a long-time folk dancer and first president of the Folk Dance Federation of California, founded in 1942, attributed the national interest in folk dance to the Depression. ‘Early folk dancers were products of the great depression’, Glass wrote in 1972, ‘they knew want and deprivation and found in friendly dancers a chance to live brotherhood.’ “

Community-based traditional social dance became an affordable entertainment in the cash-strapped Depression, a chance to overcome isolation and ‘live brotherhood’. With the collapse of the American economy in 1929, came a period of self-doubt about the value of rampant industrialization and urbanization. Regions like the South, New England, and the Cowboy West, previously seen as ‘backwater’, became re-imagined as repositories of self-sufficiency, decency, folk wisdom, and good, clean fun. In this phase, the vast majority of folk dances performed were ‘American’ (of English, Scottish, French & Irish ancestry), thanks to the efforts of dynamic researcher/instructors like Ralph Page and Lloyd Shaw.

Ralph Page and Lloyd Shaw.

In 1937, Ralph Page, who came from an extended family of callers and musicians, had been calling New England contra, round and square dances for 7 years when he published The Country Dance Book, (based on articles written between 1935-37 with Beth Tolman in Yankee magazine.) It’s one of the most enjoyable dance and Americana books ever written (thanks to Page’s sense of humor, W.F.P. Tolman’s illustrations & Beth Tolman’s writing skills). Here’s a sample: “Just how much are we enjoying the jigs, reels, quadrilles and hornpipes that used to rollick all America back in its teens? Who does the country dances now, and where?….Giving you the picture of our town Nelson, New Hampshire, the answer goes something like this: We, villagers and visitors, young and old, dance the country dances every Saturday night in the old town hall. Why? Because we’ve always danced them–for one hundred and seventy years; because there are plenty of available musicians who have grown up in the purple of the country dance tradition; because we have an inspiring caller; and there is always somebody coming along eager to join in, thus adding new faces and feet to our Saturday good times….We’d rather shake down a Hulls’ Victory, [remember above? DB] or pop a large specimen through the measures of Pop Goes the Weasel, than do all your slithery Four Hundreds in all your dancing dives in the United States“.

As well as descriptions and calls for 75 contras, quadrilles, and round dances, Page traces their European origins, including the varsouvienne, galop, polka, and schottische. In 1938, Page became one of America’s first full-time dance callers, touring five nights a week with a 10-piece band. He appeared at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, and Michael Herman (see below) released records of his orchestra.

In 1920, Colorado native Lloyd Shaw became superintendent of Cheyenne Mountain School near Colorado Springs, where he and his librarian wife Dorothy created new programs for his students. He became interested in the possibilities of dance, and taught himself European folk dances from Elizabeth Burchenal‘s books (see above). Wednesday night folk dancing became one of the school’s favorite activities, and his high school-age dancers gained a local reputation for their competence. In the winter of 1933-34 a local square dance caller asked Shaw if he could use a square of Shaw’s students to help him train for a caller competition, which he went on to win. The caller returned the favor by teaching square dancing at Shaw’s school; Shaw became intrigued with this native form of folk dance, and began intensive research into it’s history and regional variations. He praises Mr & Mrs Henry Ford‘s 1926 book Good Morning, as well as Page and Tolman‘s 1937 The Country Dance Book (see above).

In 1939 Shaw published Cowboy Dances, in which he references English dance authority Cecil Sharp’s 1917 classic, also called The Country Dance Book. After seeing a Kentucky Running Set, Sharp concluded that this Appalachian dance contained figures that preceded those recorded in Playford’s 1650 English Dancing Master, which makes it not only “one of the purest and oldest dance forms in England” but, Shaw suggests, among the earliest ancestors of the square dance. A team of his students began touring, even performing in 1940 for the National Convention of the Assn. of Health, Phys Ed & Recreation in Chicago, and in Constitution Hall, Washington, D.C.

For years, Shaw taught summer courses, attended by teachers and callers from all over the USA. In 1948 Shaw also published The Round Dance Book. A good, brief, tribute to Shaw’s contributions, called the Lloyd Shaw Era, can be found here https://web.archive.org/web/20050410230216/http://www.eaasdc.de/history/sheshawl.htm Also, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lloyd_Shaw_(educator)

Why ‘foreign’ dances?

Americans also became interested in ‘foreign’ dances because: 1. Educators’ promotion of folk dance as “an activity that symbolically promoted peace among the peoples of the world“, as stated above. 2. Soldiers, many of whom had not traveled more than a few miles from their farm homes, returned from Europe after World War I with an increased awareness of cultures quite different from their own, possibly even with a spouse from that culture, and with the knowledge that his country had a role to play on the world stage, that what happened in one part of the world affected what happened elsewhere, that we need to know what’s going on elsewhere. 3. America’s sense of unstoppable destiny was profoundly shaken by the Depression. Where had we gone wrong? What can we learn from others? People needed relief from the daily grind of their lives, and couldn’t afford to travel. How about some ‘virtual tourism’ – traveling to another place and time by dancing unfamiliar steps to unfamiliar music? 4. Novelty. Musically and structurally American folk dances were not that different from the North and West European dances that had been entering the international folk dancer’s repertoire in the since the turn of the century. Most required partners – even the ‘mixers’ that so scandalized earlier moralists. Dipping a toe in their cultures wasn’t such a big step.

1930’s – Decade of the World’s Fairs.

“American society was experiencing a multilayered crisis during the Great Depression and the government was using all available means to end it. President Roosevelt endorsed and supported World’s Fairs, seeing in them great potential for helping to overcome the economic crisis and restore faith in American society. Through this and many larger-scale social engineering projects, he adapted socialist methods to reassure the American citizens of the strength and power of the capitalist system.

Fairs provided Americans an escape from daily life, diverting their attention from the country’s economic, social, and political crisis. Just when the future seemed so bleak, nearly one hundred million Americans visited the 1933-34 Chicago Century of Progress Exposition, the 1935-36 San Diego California Pacific Exposition, the 1936 Dallas Texas Centennial Exposition, the 1939-40 San Francisco Golden Gate Exposition, and the 1939-40 New York World’s Fair. Through manufacturing fun and leisure time, the fairs created an image of a prosperous American nation whose people were happy and grateful to their country.

World’s fairs were certainly not organized to further the cause of international folk dancing, but international folk dancing was a perfect fit with the cause of the fairs, and an enactment of the vision of America they were intended to convey. In keeping with the then-current rhetoric on preservationism and exaltation of the ‘folk’ and ‘peasant’ in the midst of a crisis of advanced capitalism, folk dance was an example of the harmonious integration of differences in a multicultural society…Hardly an accurate representation of inter-group American relations, this was a carefully crafted vision that that obscured intercultural dynamics. But depicting reality was not what fairs were for….most nations showed themselves as residing in pleasant holiday-camps, where everybody had plenty, everyone was content, and everyone knew his or her folk-tunes by heart...” The World’s Fairs were multicultural Disneylands.

The Challenge of Fun.

“…Teaching people to have fun is quite a different task from teaching them folk dance steps…In order to transmit the excitement of doing folk dances, teachers had to have first-hand experience of the joy that could be found in participation. This joy in social interaction was again seen to be the strongest within traditional contexts. For this reason, Hinman began to feel the need to provide background and color to the dances that were taught…While previous folk dance teachers had turned to foreign lands for authentic material, being ‘ethnic’ was now, for the first time, perceived as advantageous, and ethnic teachers were not to be questioned about the sources of their material and information.“

“This attitude soon resulted in a reversal of roles between the students/teachers and immigrants/Americans. Instead of educated Americans of Anglo-Saxon or Jewish origin teaching illiterate, poor immigrants in settlement houses, or immigrant and native-born children in public schools, it became the norm for acculturated immigrant teachers to lead folk dance groups comprised mostly of mainstream Americans of Anglo-Saxon or Jewish origin…”

Enter the Immigrants

“…At this point in its history IFD experienced a grass-roots movement. People got together to folk dance, they organized themselves, incorporated their groups, supported their newsletters and magazines, and created whole infrastructures of the folk dance world from the bottom up. At the same time, however, top-down models of the teaching and presentation of dance material, as well as rhetoric on the importance of folk dancing to American society at large, were inherited or adopted by this grassroots movement. The movement’s practices of drawing from both the ‘top’ and the ‘bottom’ helped its growth in popularity.”

Here Balkan Fascination author Laušević introduces three of the most important persons in the history of the Recreational (International) Folk Dance movement – each a first- or second-generation immigrant, each the dominant dance instructor of his region, each having a major boost to his career by appearing at a World’s Fair. “Although the personal contributions of Michael Herman, Song Chang, and Vytautas Beliajus differed greatly in both scope and nature, they are, to the present day, widely revered as among those who contributed most to the development of the modern international folk dance scene.”

West Coast – Song Chang

Little is known for certain about Song Chang’s early years in the USA, other than that as a young man he called San Francisco home, worked on ships, and that he began folk dancing “on a German boat bound for France in 1930…As he traveled to various European countries he reputedly learned folk dances while on shore leave and from other sailors…From 1933-1937 this leader spent considerable time among Scandinavian groups learning dances from them.” Also, “San Francisco was full of opportunities to encounter folk dance, ranging from folk festivals to the city’s many ‘ethnic clubs’ that welcomed outsiders to their dance parties, to physical education classes and dance classes organized by the San Francisco recreation departments.”

In late 1937, Chang and a circle of artistic friends, including his wife Harriet Roudebush Chang, began meeting…“The social stratum of this group was very different from that of other people involved in the earlier period of folk dancing and in other locations. In Chang’s group we see a group of equals; artists/intellectuals gathering for mutual enjoyment for an activity of their choice. It may be true that Chang’s group ‘afforded an outlet for idealism and romanticism’ as stated by Henry Glass…one of the early California folk dancers. They were a group of friends who started folk dancing and decided to form an exhibition group rather than a group of folk dancers who became friends. “Chang’s group was somewhat unique among IFD groups in that (they met, DB) not to help establish social ties and a sense of community, but to learn and perform dances. Dick Crum posited (interview, 1977) that Chang treated IFD as an art, not as a vehicle for getting people together and socializing. ‘The product was more important than the producer. All the dances were more showy, more for spectacle…you are all there to achieve perfection in this dance that he was presenting that evening.’ Judging by the record of the group’s activities, public presentation was clearly an important part of its raison d’être. Interestingly, folk dance continues to be more performance-oriented on the West Coast than in other regions.”

“In early 1938, Chang’s group moved to the Green Lantern Cafe…one of the first folk dance venues to resemble ethnic social clubs in which folk dancing took place over the course of an evening along with dinner and drinks…Song Chang did most of the teaching at the Green Lantern…the music for the dances came from records provided by Song and Harriet Roudebush Chang”...later…”Chang decided to move the classes to a spacious studio on 415 Broadway, creating some friction within the group. At that point Virgil Morton began teaching the classes at the Green Lantern and many in the group began frequenting both places. The large dance hall at 415 Broadway…proved to be a boon when we started attracting notice at the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1939.”

“Participation at the World’s Fair at Treasure Island was a turning point not only for Chang’s International Folk Dancers, but for the development of folk dance in California and in the United States in general. The Golden Gate International Exposition opened in May of 1939, and Chang’s IFD had a standing engagement during the fair season...The tremendous public exposure they got at Treasure Island is most clearly seen in the subsequent growth in the group membership.

Indeed in 1939-1940 folk dance groups mushroomed throughout the Bay area and Chang, Morton and many other folk dance instructors stemming from Chang’s group had their hands full organizing and teaching classes. In the early 1940’s, membership in Chang’s group grew to the point where, according to Morton, it was not unusual to have a hundred people in a class. ‘…it is now possible to dance seven nights a week, from San Anselmo to San Mateo, with a group of Chang’s’ The Folk Dancer bulletin reported in November of 1941. In early 1940, Song Chang resigned from teaching and gave up his presidential duties because of a personal conflict with a member of his group, according to Morton…Although the group continued to bear his name, Chang himself seldom participated.

‘Authenticity’, ‘Purity’ and the Folk Dance Federation of California

“Virgil Morton took charge of the instruction of new members as the first official teacher…At this time the group met in a hall that was shared with the Poppy Social Club, a group of White Russian intellectuals who taught the group some of their dances. ‘Striving to keep folk dancing in its pure ethnic form,’ Virgil Morton urged ‘members to visit the various ethnic groups in San Francisco to witness at first-hand the various dances.’ he was teaching.“

“Under Morton’s leadership, Changs IFD was concerned ‘that deviations did not creep into the dances that had been learned from various ethnic sources. To help ensure that this ‘purity’ of form and character would be maintained by the new groups that were forming as well as with our own members…we wrote down the dances that were used by Changs…’ What Morton describes was an attempt to gain control over the growing number of groups that branched out of Changs IFD. Writing down the dance instructions was meant both to prevent deviations and variations from one group to another and to accumulate an authoritative core repertoire. This was the first step toward the formation of the Folk Dance Federation of California.“

“As clubs grew in number and membership, more attention was given to ‘authenticity’ and ‘purity’ of sources, as well as to accuracy in performance...Quoting Morton; ‘In a group interested in performing accurately the dances of various nationalities it is important to know as much as possible about the wearing apparel of those nationalities, as well as other facets of their native culture. To provide easy reference material for new members, and also to eliminate to some extent the necessity of verbally lecturing on these points in the classes, it was decided to form a Research Committee…”

“The explosion of folk dance in the Bay Area complicated communication between groups and made it harder to maintain a sense of unity and consistency throughout the increasingly vast membership. The establishment of a bulletin in February of 1941 [with Morton as midwife-DB] called The Folk Dancer (later to be named Changs) was one step towards addressing the situation”...Morton; ‘My purpose was…to attempt to break down some of the hackneyed opinions people so frequently form in regard to nationality and religious backgrounds other than their own. The bulletin was also to be used as a news source regarding meetings and items of general interest’... Unwittingly, Changs magazine and others like it often did more to create new stereotypes and affirm old ones than they did to help deepen dancers’ understanding... In order to make the information more colorful, dances that somehow incorporated a story were favored. ‘Americans want a bedtime story with every dance’ said Dick Crum about the persistence of this practice (Interview, 1977). ‘Those stories are always around, and they are made up by anybody. This is an antiquated idea that probably came from ballet, where the dance tells a story.’ “

“The second, and much larger, step toward the unification of Californian folk dancers was the establishment of the Folk Dance Federation of California in 1942...The impetus to form a federation of all the California folk dance groups came from Henry Buzz Glass, a member of Changs International Folk Dancers since 1940. He became the the organization’s first president on June 14, 1942..Echoing the goals of The Folk Dancer, ‘the objective of the organization was not only to promote folk dancing but to exercise control over the many versions of dances that were being introduced to different groups.’ This organization became the heart of the folk dance movement in California and had a significant impact on the development of folk dance in the United States in general.”

“The most important contribution of the Federation on a national level is the work of its Research Committee. Lucille Czarnowski of the University of California, Berkeley, was its first chairman. The committee not only published numerous volumes of folk dance books but, as Glass points out ‘a format for writing dances was established that was later to furnish a working structure for other writers.’ Many teachers and folk dance groups across the country used the folk dance books published by the FDF of California as a source of new material.”

“The control the Federation established over the numerous folk dance clubs enabled it to approve dances and dance instructors alike. The organization intended, ultimately, to establish a unified folk dance repertoire [emphasis mine, DB] that would make it possible for folk dance enthusiasts across the country to dance in exactly the same way. This would prevent dance teachers from inventing dances or creating a repertoire that would be particular to a specific club or instructor.“

Middle America – Vytautas Beliajus, ‘Vyts’

“Vitautas Finadar Beliajus, commonly known as Vyts, emerged as a folk dance leader in the early 1930’s in the Midwest. As a fifteen-year-old boy Beliajus immigrated from the village of Pakumprys, Lithuania with his grandmother. In September 1923 they settled with relatives in a Lithuanian neighborhood in Chicago. It was here that Vyts’s folk dance career began.“

“Trying to trace Vyt’s path in the folk dance world is complicated by the large amount of undocumented and uncritical information on his life and work floating around in numerous articles in folk dance books and magazines…Vyts’s own writing is problematic for the researcher, as conflicting information appears not only from one magazine issue to another, but sometimes within the same article...Vyts liked to give the impression that the majority of his international folk dance repertoire was acquired in Lithuania, learned firsthand…Whatever the status of Vyts’s knowledge of folk dance before settling in the United States, there is no doubt that his repertoire expanded in Chicago…Vyts was directly associated with Chicago settlements (Settlement Houses – DB), which may be where he was first introduced to the idea of international folk dance, possibly even where he got his first folk dance training. The following excerpt from Viltis is illustrative of the depth of Vyts’s involvement with the Chicago settlements:”

“…Eventually even I and my group danced and presented programs at the Hull House. Later I myself became involved in Settlement House work. I had a wonderful group of Polish kids at Northwestern University Settlement House…I worked with Mexican kids at the Henry Booth House, at Howell House with Croatian and Czech young people, and with Lithuanian kids at Fellowship House…”

“Mary Bee Jensen explains how, in Chicago, Vyts ‘had an exciting opportunity to meet others from many nations. He first became interested in Mexican culture and folk dances, then soon began to include Italian and Hindu dances in his repertoire.’ He then ‘became deeply involved in Hassidic dancing’ (in Casey, 1981: 11). ‘The first I sought out in my second year in Chicago were the Moslem Arabs, then the Italians, Sephardic Jews, Croatians and others’ writes Vyts in Viltis…This was not a usual route for a folk dancer. Dick Crum saw Vyts as a follower of Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn, pioneers of modern American dance who, with their Denishawn dance company, experimented with movement based on ethnic and tribal dance. Judging from Vyts’s approach to dance, typified by exoticism more than a ‘back to nature and cultural roots’ philosophy, as well as from his interests, biographical details, and pictures of him in costumes emulating those of Denishawn, their influence is quite apparent.”

“Vyts’s teaching career probably began in the early 1930’s and was focused first on Lithuanian dances. He organized the Lithuanian Youth Society in Chicago, and with this group participated at the Chicago World’s Fair A Century of Progress International Exposition in 1933. Beliajus was also hired by the Chicago Park District to teach teach folk dancing, beginning in 1936. ‘I taught various native dances varying with the ethnic population living around the parks. Turkish ‘Havassi’ dances to a Ladino group, then the current Palestinian [early Israeli-DB] dances to Jewish groups, Polish, Russian, Latvian, Lithuanian, German and Ukrainian.’ (Beliajus in Casey, 1981: 91). Like other prominent folk dance teachers during the New Deal, Beliajus worked for the WPA. In fact, between 1936 and 1938 Vyts was the editor of the first folk dance magazine, Lore, published by the Chicago Park District under a WPA project.“

“By the late 1960’s, Vyts claimed to have taught ‘in every state except Hawaii and…in Canada and Mexico’…Between 1937, when he started teaching outside of Chicago, and 1940, ‘he’d taught at over two hundred universities, colleges, and institutions and had sparked nationwide interest in folk dancing’ (Jensen 1981: 12). Touring would become much more common in the next phase of folk dance development, when teachers began to specialize in dances of a particular area of the world. Soon it would become common practice for teachers to travel from one folk dance club to another. This development demanded of teachers that they come up with new material to teach from one tour to the next. Under these circumstances teachers found their own ways to feed the growing folk dance market. ‘Vyts taught dance after dance after dance, and would never say where they were coming from, and nobody ever asked him’ Dick Crum commented. (Interview, 1997). ‘he would never tell his sources. He enjoyed the impression that everyone had, that he somehow came to the U.S. with all this knowledge…He was often forced into situations where he was called on for expertise that he did not have.’ “

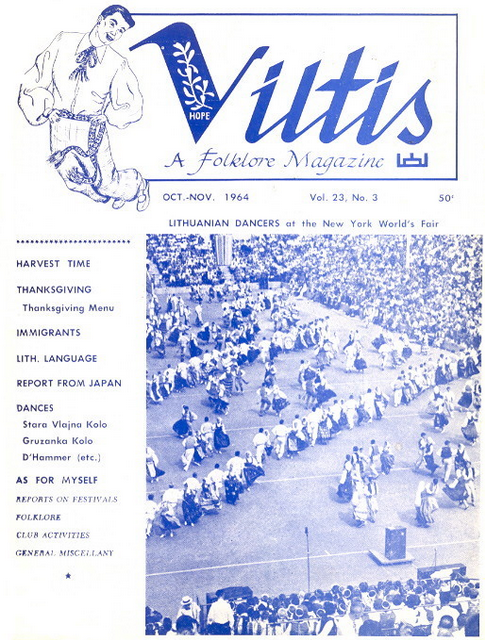

Viltis

“Beliajus’s unique and possibly largest contribution to the folk dance world is his folk dance magazine Viltis (‘Hope’ in Lithuanian). It started as a mimeographed letter for servicemen in May of 1943 in Fairhope, Alabama, where Vyts was teaching at the time. He described the original purpose as ‘to keep up with the activities of our friends in the Armed Forces scattered throughout the world, and to exchange news’…It was not until 1944, when Viltis first appeared in printed form, that it became a folk dance magazine, an amateur publication created to suit the needs of international folk dancers. Viltis remained in print six times a year and gained a national and even international readership over the years.

One could argue that the feeling of community Michael Herman endeavored to create through an emphasis on sociablilty in folk dancing Vyts realized through his magazine. Readers were encouraged to send news and announcements to the regular column ‘Among Friends,’ which included information and trivia from the private lives of folk dancers. This helped the readership keep in touch with each others’ lives and the folk dance world in general, engendering a feeling of community, continuity, and cohesion among people who were not regularly in touch or may never even have met. In this manner Viltis presaged the Internet chat rooms and list serves that were to develop half a century later.

“In another regular column, ‘As For Myself,’ Vyts offered reports on his teaching tours, travels, and visits with various folk dancers, as well as very personal news about his frequent ill health, which gave readers the sense that they knew him. In the eyes of many of his ‘followers’ he became an embodiment of American unity in diversity. “

“The magazine also carried folk dance news and articles on related subjects, including costumes, customs, and recipes. Vyts’s editing was uneven, or, rather, the quality of the articles varied considerably between authors. Many articles were full of errors, misinformation, and speculation. Vyts proudly called this Viltis’ ‘original personal journalism.’ This type of personal writing, with its feeling of in-group camaraderie, is characteristic of many other folk dance publications, including Herman’s Folk Dancer, Northwest Folk Dancer, and Folk Dance Scene in Baton Rouge, and is a manifestation of the general attitude of democracy and supportiveness.

East Coast – Michael Herman

“Michael Herman is often acknowledged as the father of international folk dance in the United States. As Dick Crum [see 3rd Phase for article on Crum – DB] commented, ‘Nobody contributed to the overall development of recreational folk dancing as much as Michael Herman’ (Crum Interview, 1997). Herman stands out from the other folk dance giants because he was not only a dancer but a musician, competent organizer, publisher, writer, and record producer.”

“Michael Herman was born in 1910 in Cleveland, Ohio to Ukrainian parents. His family apparently moved frequently when he was young, so he lived in many different ethnic neighborhoods: Polish, Ukrainian, Czech, Serbian and Romanian…If Herman was exposed to folk dances of various ethnic groups in the ethnic neighborhoods of Cleveland, it was only within the Ukrainian community that he was active as a performer, as both dancer and violinist…The first crucial event in Herman’s folk dance career was joining the Ukrainian Folk Dance Group of Cleveland under the direction of Vasile Avramenko. With Avramenko, Herman not only acquired his first professional dance training but he learned how to teach and notate dance instructions, skills that would be in extreme demand in his later career. As an able young dancer Herman became Avramenko’s assistant at the school and, when he decided several years later to move to New York, he came to Avramenko’s studio in Manhattan. ‘I was invited to be a teacher for him in New York. I was his assistant teacher’…Both Michael Herman and his future wife and teaching partner Mary Ann Bodnar, a member of Avramenko’s folk dance group in New York, participated in Ukrainian festivals at the Metropolitan Opera House and Carnegie Hall...”

“It was in Avramenko’s school that Michael and Mary Ann learned most of their Ukrainian and Russian repertoire. The Hermans adopted Avramenko’s normative and prescriptive way of teaching, but used it only when they taught the Ukrainian repertoire in their future international folk dance programs.”

“‘When Mary Ann or Michael would teach Ukrainian dance, it would differ from any other kind of dance they taught. There was only one way to position your arms in Hopak…’the hand of the woman in Hopak goes like this, under a certain angle, six inches apart, ‘ etc…And there would be a reason for it: ‘The women in Hopak hold their arms like this so they can hold their beads.’ When the Hermans would get up to teach Hopak they were two different people. Mary Ann would drop the needle on the record and say: ‘This dance does not belong to you, it belongs to the Ukrainian people and you need to return it to them in the same form.’ But I wondered, how can she say that and then the next day put on a dance from somewhere else with no style, no detail, where whatever you did was okay. (Crum, Interview, 1997)”.

“Crum’s vivid account is significant in many respects. First of all it tells something about the style of teaching folk dance that folk ballet masters like Avramenko adopted. The Hermans, as Avrmenko’s successors, seemingly treated Ukrainian folk dance with the rigidity, precision, and discipline of movement found in ballet. One aspect of this normative and ‘scientific’ approach to interpreting of folk dance was the rationalization of, and attribution of meaning to, dance movement, turning the dance into a narrative. This created narrative contributed to the value of folk dance as a cultural signifier. The Hermans learned their other dances under different circumstances and without this embedded narrative. Hence, these other dances were transmitted with more freedom of movement and interpretation. Another factor in this double standard is that teachers, the Hermans included, are often the most prescriptive and normative about the material they know best. Disconnectedness from the material and the culture in which it was created tends to result in teaching without attention to style and detail.“ [emphasis mine, DB]

“In the 1930’s Herman attended various ethnic events around New York City…he joined various ethnic bands and learned their melodies on the violin…Because of his ability to dance their dances, many ethnic groups adopted him as one of their own…Mary Wood Hinman [see The Pioneers, above – DB] was one of the ‘truly influential people’ in Michael Herman’s life. When classes at the New School of Social Research began, Herman was asked to teach, as well as to help various ethnic groups in their presentations. ‘Ethnic groups were not used to teaching Americans their dances, and often asked Michael Herman to help them’ He also wrote down the music and directions for many of the dances...Michael Herman’s skills were in high demand in the 1930’s in New York. Unlike other ethnic dancers he had the advantage of being fluent in English and professionally trained in both music [Julliard – DB] and dance.”

“Throughout the 1930’s, Michael Herman was very active in New York folk dance circles, but more as a facilitator than a leader. The moment of transition in his personal career, and in the history of international folk dance on the East Coast, was the New York World’s Fair…As it happened in San Francisco in 1939, folk dancing took off after the fair in New York.”

New York World’s Fair, 1940

“In addition to the ‘nationality days’ in which ethnic performing groups were showcased, Michael Herman taught general folk dances to fair visitors at the Commons… Herman attributes the success of the program to the fact that ‘it was based on the realization that folk dances, one of the most colorful contributions by immigrants to this American culture, are NOT to be watched just as colorful entertainment, but are to be PARTICIPATED in’. Michael Herman proved to be an excellent choice for the job of directing Folk Dance Evenings at the Common. Music for the dances was provided by Mary Ann Herman on the piano, Walter Ericksson on accordion, and occasionally, Michael himself on the violin, when he wasn’t running back and forth cajoling casual fair-goers to join the dance. “This vision of humanity, joyful and harmonious, was very attractive and many were eager to participate in its creation. The interest in Folk Dance Evenings at the Fair ‘grew so rapidly that the crowd would number over 1,000 at times. In fact, people began to come to the fair just to dance.‘ “

After the fair, Michael “saw a need to continue the program in New York…the beginnings were less than spectacular…but Michael persisted…After moving to the Polish National Hall, also called Arlington House, in 1941, ‘folk dancing really took hold, without advertising, just word of mouth, the group grew and grew, until instead of just one night a week…they were meeting three nights. With the move to Arlington Hall, the first issue of The Folk Dancer was issued in March 1941. Note that only a month earlier, in February, Changs International Folk Dancers in San Francisco published the first issue of their periodical, also called The Folk Dancer. Michael Herman edited and published his magazine monthly from 1941 to 1947, when the publication was discontinued for financial reasons.”

Folk Dance House, Camps

“The opening of Folk Dance House in 1951 was a milestone in the history of folk dance on the East Coast. There, Michael Herman, more than ten years after the end of the World’s Fair, was finally able to create his own schedule and have a place to call his own. ‘It was a very large space…the legal occupancy was 280 people…’Having an actual physical space that belonged to the folk dancers enabled them not only to decorate it and transform it into a folk dance oasis, but also to deepen their feeling of being a community...Throughout his career, Michael Herman had strongly emphasized the social aspect of folk dancing. “Michael had this idea of the dance being specifically designed to make friendships happen and to make people happy…Michael would say style was important, but looking people in the eye and having fun was more important.’ Crum, Interview, 1997).

The schedule at Folk Dance House grew to include various age groups and levels of experience. ‘There were classes of all kinds, every day of the week, family programs for children, parents and grandparents on Sunday afternoons’ (Herman, notes). ‘There was even a type of daycare with ‘arts and crafts, stuff to do’ for children while parents were dancing. ‘Schools were bringing bus loads of students to learn the dances and finger the costumes. There was a teenage program on Saturday afternoons with high school boys folk-dancing for five hours straight.’ “

“The well-known recreational leader Jane Farwell approached the Hermans in 1938-39 with the idea of having a camp for adults in which folk dance, costumes, crafts, and cuisine would be integrated into the daily programs. ‘We helped her organize the first folk dance camp in the country in 1940 in Oglebay Park, West Virginia.’ Jane Farwell also initiated the Maine Folk Dance Camp, which Mary Ann and Michael Herman went on to take over and run for more than four decades.

Folk Dance Records

Although sound recordings were invented in the 1880’s, it wasn’t until the 1920’s that they were purchased on a massive scale. They were still relatively expensive, however, so the Great Depression greatly depressed record sales. Radio and live music were the formats of choice until World War 2 (1939-1945) simultaneously decreased the number of live musicians available (the draft) and increased factory workers’ wages, making records affordable to the masses again. Record companies produced popular dance music – ballroom dance and ‘country’ dance (squares, contra, round). Almost no one was making records for ‘international’ folk dance until Michael Herman.

“One of Michael Herman’s most enduring and unique contributions to the folk dance world is the series of records that, in many places, are still used in dance classes…Herman realized that music for the dances had to be readily available, as hiring musicians for dance classes was not only costly but difficult. Ethnic musicians were accustomed to playing their own dances but not to traveling the world, so to speak, from one dance style to another…Herman’s first album, recorded in the mid-1940’s, contained Mexican, Lithuanian, Danish, Czech, Swiss, Polish, & Estonian dances [All couple dances – DB]. Performed by Michael Herman’s Orchestra, a group assembled with the help of Walter Ericksson, who had played with Herman since the 1930’s, the recording was met with considerable enthusiasm. The response was such that…Herman went on to produce a series of some 300 recordings on his own Folk Dancer label, including releases by ethnic orchestras such as Kostya Polyansky’s Balalaika Orchestra for Russian dances, Banat Tamburitsa Orchestra for Yugoslav kolos, Tom Senior’s Irish Orchestra, The Ralph Page Orchestra for American squares and contras, and many others. These recordings were a huge step forward from the old days of skeletal piano notation such as Chalif’s (see The Pioneers, above). The recording of ‘ethnic’ orchestras in particular exposed dancers to elements of style that must have been revelatory.

“One of Michael Herman’s first recording projects was for the Methodist Church. He was contracted by the General Board of Education of the Methodist Church to produce a series of what was initially to be six records for their recreational program. Titled “The World of Fun” (1947), the records were accompanied by a 25-page booklet of dance directions, most of which were written by Herman himself.“

“The booklet assured the reader that the records ‘can go a long way toward helping your group to appreciate what other peoples have contributed to the fun of the world….In their own right they are fun – these folk treasures from other countries. Wise ministers, counselors, and youth leaders of recreation will of course recognize this.’ Distanced from their culture of origin, folk dances were reduced to the single category ‘fun’. As ‘contributions to the world of fun,’ folk dances did not belong to the people that created them or danced them, but to everyone. Responsibility to original sources, or even interest in them, was not an issue here. The details of a particular style were of little interest to the musicians and folk dancers alike, and the significance of the dance as ‘international’ was primarily symbolic. The records were, above all, utilitarian. It was important to make the rhythm straight and the tempos comfortable for dancers so the records could do their job.“

“As it was commissioned by the Methodist Church, the music was ‘toned down’ and dances were called ‘folk games’ to discourage an association with popular dancing. Michael reminisces that ‘Only three pieces were used in the orchestra,and they were admonished to play the music ‘straight’…not too frivolous. Can you imagine playing Irish Washerwoman for five minutes without changing keys or varying the tune?”

Contemporary listeners, with the benefit of virtually unlimited access to the world’s music, might find even the liveliest of Michael Herman’s orchestra recordings monotonously pallid. Most feature the same instrumentation and more or less the same style, regardless of the genre. However in their day these records provided an exciting opportunity to hear dance tunes from many cultures in one place and, perhaps more important, provided a steady rhythm that contributed to the growth of the folk dance movement.”

Personal Evaluation of the Immigrant Phase

As in the first phase, this second phase was little interested in the ‘foreign’ culture and the traditional social significance of a particular dance, but rather on the results these dances could achieve if practiced in a modern American context. [For contrast, click https://folkdancefootnotes.org/begin/folk-dancers-type-1-of-3-traditional/] Folk dancing was becoming associated with a desire to demonstrate to the world (and to ourselves) that dance transcended culture. Everybody could enjoy everybody else’s dances, at least if ‘enjoyment’ was framed in American-based ideology, which defined finding common ground, ‘getting along’, as more important than expressing traditional values. The world’s dances were seen as belonging to the world; free for anyone to mimic, enjoy, adapt to their own needs. Central to the ‘anyone can dance anyone’s dances’ idea was the projection of ‘our’ reason to dance – fun – on to ‘their’ reason to dance – ‘for fun, I suppose; after all, we’re all the same under the skin’.

The Immigrant Phase also began the proliferation [bottom-up] of folk dance clubs throughout the nation and with them, the need to communicate and co-ordinate activities. Though much of this activity had a positive effect in building a nationwide movement, one such organizational effort [top-down] produced what in my opinion was a questionable result.

“The control the [California Folk Dance] Federation established over the numerous folk dance clubs enabled it to approve dances and dance instructors alike. The organization intended, ultimately, to establish a unified folk dance repertoire [emphasis mine, DB] that would make it possible for folk dance enthusiasts across the country to dance in exactly the same way. This would prevent dance teachers from inventing dances or creating a repertoire that would be particular to a specific club or instructor.“

Was “to establish a unified folk dance repertoire” a good idea?

Leadership, and/or control, are primary needs of social animals like humans. We like to come to a consensus so we can act together in harmony. We approve of a leader who can marshal consensus over creative deviation when we perceive that deviation leads to a lack of unity among the group. In a traditional pre-literate rural society, [the basis of ‘folk’ culture], control/leadership is granted to the head of a multi-generational family unit – the repository of oral traditions, experience, and wisdom. Dances are handed down from generation to generation, based on the memory of the elder’s youthful experience of learning ‘how it was done’. There was little questioning that experience, because few were around to counter the elder’s evaluation of his youthful learning. The basic form of a dance thus remained similar from generation to generation. However, the basic form of a dance was, in the words of John Uhlemann, “a structure into which you pour your dance, not a single step“. Individual expression was permitted, even encouraged, so long as one didn’t interrupt the flow of a dance (bother your neighbors.)

The idea of establishing a unified folk dance repertoire across a region, state or nation was simply not conceivable in such a traditional culture. It is the product of hundreds of years of cultural and intellectual evolution, a solution to problems that didn’t exist in a traditional culture with no mass communication, weak decentralized government, and little personal mobility.

20th century Americans, on the other hand, were more than family members – they felt part of a city, a state, a nation – they had intellectual ‘kin’ hundreds of miles away, united by a national media (newspapers, radio), and they appreciated those ‘kin’ being on the same page. They were highly mobile, traveling easily across thousands of miles. Plentiful manufactured goods, based on mass production of standardized parts, was an American invention and a key to its prosperity. Mass communication, and its outgrowth, “manufacturing consent”, was key to the unity of opinion that made America a formidable adversary of totalitarianism. Americans naturally took to the idea of a unified folk dance repertoire. America ‘won’ WW2 due in part to voluntary suspension of individuality to achieve a common goal, and that leftover spirit of co-operation was what made a unified folk dance repertoire an easy sell. Folk dances came to be seen as another product that could be reproduced uniformly across cities, states, regions.

However there is an irony associated with a top-down control approach to a problem that didn’t exist in a traditional culture, whose very number and variety of dances, which Americans found so appealing, were due to a lack of such control. An unintended consequence of such control was the dis-empowering of individual dancers and teachers to feel they could express themselves while dancing (unless they had sufficient expertise in styling, etc.) Dis-engagement of individual personality from dance experience inevitably resulted in a more passive, follow-the-leader type of dance experience. This approach dovetailed with the anyone-can-dance approach. You don’t need to know much about dancing, or folk culture, just follow the leader.

The opinion below was written by Richard Duree, and found in this source: https://www.sfdh.us/encyclopedia/real_vs_choreographed_folk_dances_duree.html

“I can’t resist adding my own concerns about this ever-lasting issue. It might help to take a look at how the whole folk dance “movement” started and what issues shaped recreational folk dance as we know it. At least as far as California in particular, and the country in general, is concerned, trace it back to the Stockton Folk Dance Camp, the grand-daddy of them all. When Lawton Harris started the camp back in 1948, he set down a series of rules and conditions that put several restraints and requirements on teachers. Some of them sound pretty strange now and were certainly not conducive to taking a “folkloric” approach to the dance. I don’t know what they all were, but a couple I can recall: “The dance must not have been taught anywhere else” and “There must be no variations to the choreography.”

There were others, but just these two tended to put a rigid and artificial face on the folk dances coming from the camp, which for a long time, was THE fountainhead of material for the recreational folk dance community. Lawton Harris was not a folklorist; his concern was in creating a dance form in which everyone would dance exactly the same thing everywhere.“

I’m not suggesting such control should not have been attempted. But I am suggesting that such control is more a reflection of 20th century American sensibilities than of the traditional folk sensibilities being mimicked, and helps exaggerate differences between the attitudes and performance modes of traditional and recreational folk dancers.

As any folk dance researcher knows, a dance varies in execution from dancer to dancer within a village, from village to village, from culture to culture doing the same dance, and across national boundaries – many of which have moved over time. This matters little to a ‘villager’, as he or she seldom travels far, therefore seldom encounters much variety.

However someone introducing a ‘new’ dance at Stockton must decide which of the many variations he or she has encountered will be the ‘official’ version of the dance, thereby leaving the impression there is much less variety than is in fact the case. The instructor is discouraged from teaching different variations in different locations, which leaves the impression that by mastering the Stockton version of a dance, one has learned all there is to know about that dance – just follow the ‘expert’. One’s success is not measured by how one expresses one’s self in the dance, but by how accurately one mimics the instructor, how faithfully one follows the written instructions. Even if what one does is within the range of variations done by ‘village’ dancers from adjacent regions, if it’s not on the page it’s ‘wrong’. This is not the fault of the instructors – they have to follow ‘guidelines’.

Learning to dance this way is like learning to paint. The ‘folk’ artist learns painting like he/she learns dancing – by watching elders, learning to mix colors, imitating, learning how to organize a space, practicing traditional patterns – but ultimately by applying to a surface what the artist wants to see – what ‘looks good’. The recreational dancer has not grown up in the folk tradition – everything is foreign – that’s why it’s appealing. He/she can only produce dance results similar to a ‘villager’ by reproducing a pre-set pattern. Having an instructor tell you where to put your feet is the dance equivalent of following the directions to a paint-by-number set. The visual result may resemble a ‘folk’ painting, but one learns little about how to paint.

However, the upside to the recreational style of learning dances is it’s easy – a slight amount of practice and you’ve ‘done’ that dance. Once you’ve ‘done’ it you’re ready for another, and another. Since you still know little about ‘village’ dance practices, you come to expect ‘dancing’ to be ‘learning from an instructor’. The two are inseparable.

Folk Dance was not very International

It is important to recall that during this period – the 1930’s & 1940’s, ‘folk’ dance meant to most people in the USA, AMERICAN folk dance; square, contra, and round dances from the South, West, and New England. Even among those interested in ‘International’ folk dance, the ‘world’ was still conceived mainly as countries of Western European civilization. People of color and their cultures were considered quaint at best, more often downright uncivilized. Even the Balkans and the Middle East had yet to become popular. International Folk Dancing was not very international.

In Michael Herman’s pioneering folk dance record series “The World Of Fun” (1947), the ‘world’ consisted of Hungary, Switzerland, Lithuania, Austria, Ireland, Denmark, Germany, the USA, Mexico, England, Russia, Belgium, and Finland. Nothing from the Balkans, Middle East, Asia, Africa, the Pacific, or South America.

The leading instructors of the day – Chang, Beliajus, & Herman – were recent immigrants who learned their dances in the immigrant community; not by formal instruction but by dancing with and imitating their peers. It was the same process as in traditional dance cultures, and the dances learned and passed on tended to be simple ‘living’ peasant dances. Those immigrants in turn were adapting to American ways, and their ‘traditional’ dances, as practiced among resident immigrants, were evolving toward ‘Americanization’, as when local bands played to many different ethnic groups, blending elements of one culture with another, or incorporating ‘American’ instruments to give the music a sound more acceptable to newly-American ears who didn’t want to appear backward. In turn, the instructors, in order to make the dances (and themselves) more acceptable and ‘fun’, to their mainstream clients, tended to idealize the source cultures, minimizing cultural animosities and practices that were out of sync with American values. These cultural ambassadors therefore contributed to the notion that ‘we’re all the same under the skin’ and that one culture was much like any other, so ‘we’ were welcome to dance ‘their’ dances using the same assumptions we’d use with our own. They created bridges that could be freely traversed in both directions. “Virtual tourism” had never been easier.

1949 Stockton Dances

The 1949 syllabus for the 2nd annual Folk Dance Camp at Stockton, California, lists 61 dances from 14 countries – half (31) from the USA, 15 from England, Scotland & Ireland, 8 from Austria, Germany, Russia, Czechoslovakia, & Denmark, 3 from Mexico, 1 each from Italy, Argentina (tango was still considered a folk dance), Ukraine, & Croatia (“Croatian waltz”). PERCENTAGE OF OF NORTH & WEST EUROPE + NORTH AMERICA TO TOTAL DANCES 92%. Most dances of the Immigrant Phase required partners, the default formation for Western civilization, [though seldom used elsewhere.] Only 5 dances out of 61 did not require a partner. One was an English trio of 3 men, the other 4 were Morris dances. PERCENTAGE OF PARTNER DANCES; 92%. Almost all of the music for dancing utilized records, though not necessarily records produced exclusively for the dance taught. It was a common practice to list suitable substitutes.

Partners was also the default combination for American square, contra, and ballroom dances, so Americans already understood the social milieu involved in this kind of dance – courtship, and its limits imposed by society – the culmination of hundreds of years of Western European cultural evolution. [For more on this topic, click https://folkdancefootnotes.org/begin/why-do-north-west-european-folk-cultures-have-mostly-partner-dances-while-south-east-europe-has-hardly-any/] In partner dancing the focus is on the couple – eye contact with your partner is expected. Dancers adapt to their partner’s style and abilities – what other couples in the group are doing is of secondary importance. Focus is mainly on socialization – the ‘chemistry’ between you and your partner. This focus varied little, whether dancing an American square, an Austrian Ländler, or a fox trot.

The Importance of Live Music

It is equally important to recall that most dancing in this era was done to live music. I maintain that dancing a Bulgarian Horo to live piano music is closer in spirit to traditional Bulgarian dance than the same dance accompanied by an ‘authentic instruments’ record. The music coming out of the piano may bear no resemblance to Bulgarian instrumentation, the melody may not even be Bulgarian, but if the pianist is responsive to the energy of the dancers, a connection is formed that a record cannot duplicate. The pianist can repeat, amplify, change melodies, accents, tempos. The music comes alive, unique, and the dancers are more actively engaged in it – the dance becomes a collaboration between musician and dancer – something different every time, rather than a passive repetition of a fixed formula. Individual dances tend to last longer when performed to live music, and though the footwork may not vary over that stretch of time, interest is maintained by the unpredictability of musician-dancer interactions, the creativity of individual styling and the ebb-and-flow of ‘chemistry’ among dance partners. Fewer dances are required to fill an evening of ‘fun’. Likewise, fewer ‘exotic’ instruments are needed to maintain dancers’ interest.

In my opinion, the second, ‘Immigrant’ phase of the history of recreational folk dancing in the USA was the only time when most Americans danced in the same manner as the ‘international’ cultures they were emulating. This was in part due to the similarities of American culture to the Northern European cultures imitated at that time; their both doing primarily couple, quadrille and contra formations of fairly simple ‘village’ dances, and to their both using live music, which created similar expectations and dynamics on the dance floor. In most cases, dancers were ‘dancing’, rather than ‘doing dances’. [For more on this distinction, click https://folkdancefootnotes.org/begin/how-balkan-folk-dances-are-made-arranged-folklore/.]

Ironically, Michael Herman [among others], by popularizing folk dance records intended to enable the spread of folk dancing, unwittingly contributed most to its fundamental transformation – a transformation that Herman himself lamented. Because recordings produced the same result every time they were played, boredom with that music came much more quickly; ditto for the dances the recordings represented. Along with those recordings, Herman included dance notes – instructions for doing the dances, which also helped standardize the way dances were performed. The record-and-notes combination created an authoritative ‘package’ that gave confidence to anyone, with or without an ‘ethnic’ background, that they, too, could perform and even teach those dances. Author Laušević concludes her discussion of the second phase of recreational folk dance history with this ominous look to its future:

“As the folk dance infrastructure grew, a constant influx of new dances became a necessity. Michael Herman was greatly disappointed by these developments: ‘We started teaching everybody in 1940 and all those years it’s spread to every city. New people, like my teenagers, wanted to teach. They want to become famous, too. When there are three teachers in the same city…everybody will go to the one that will teach new dances. Then the other teacher says: ‘Gee! I have to have somebody teach me new dances.’ They assumed that all of the new dances will be of the same qualities. And you get to the point where it is stupid.”

“These words imply much about problems the movement encountered as a result of its growth. With the increased number of teachers there came competition for class membership, and teachers began to fight for their share of the market. The demand for new dances often led teachers to make up new dances and stories to accompany them. Providing new material, dances never before presented to Americans, became not merely a fashion but a demand. Groups came to rely on this constant influx of new material to keep them going. Herman’s comments both criticize these new teachers with their new dances of untried quality and justify his own repertoire. At a time when many younger teachers had begun traveling abroad, doing some ethnographic research and learning new dances, particularly in Balkan villages, Herman was unwilling or unable to alter his approach.”

This analysis by Laušević, though fundamentally correct, underestimates the role folk dance records played in the movement’s explosive growth. The number of new groups and teachers could not have grown so dramatically if each had to find their own competent musicians to accompany them. For newcomers to dancing, the familiarity and clarity of practicing to the same record made learning dances easier. The demand for new dances would not have been so great if people didn’t tire so quickly of the ‘same old records’, and if records weren’t limited in length (Long Playing – longer than 3 1/2 minutes – records did not become widely available until the early 1950’s.) New dances would not have been so easily created by teachers if they didn’t have an ever-increasing supply of new music in a repeatable format.

Summary of the Immigrant Phase: 1930’s – 1950’s

‘They’ (in our midst) are like ‘us’ and help ‘us’ have fun.

The second phase of the history of Recreational Folk Dancing was definitely a grassroots movement. Ordinary Americans, often recent immigrants, began teaching the dances of their culture, and dancing the dances of other cultures, for their own pleasure. Their enjoyment and enthusiasm was witnessed first-hand by ‘settled’ Americans, who wanted to join in the fun. Many leaders of ‘top-down’ institutions – schools, physical education departments, recreation departments – began to stress enjoyment as the prime motivator for folk dance – dancing from the inside out.

The broader appeal of ethnic and native folk dancing for fun was increased by a questioning of the USA’s values during the Depression, and an interest in other cultures, sparked by visits to World’s Fairs where many engaged in ‘virtual tourism’ when they saw folk dancing for the first time. Because the new breed of immigrant dance leaders were teaching from their personal experience of immigrant communities, they were better able to convey the positive social aspects of folk dance to ‘outsiders’, turning exercise into fun. When Americanized immigrants became the teachers, their new-found authority helped turn ‘they’ into ‘we’ – people who can talk to us and have something we want.

Three first- or second-generation immigrants were especially important to the explosion of interest in recreational ethnic dance in this period – Vyts Beliajus, Michael Herman, and Song Chang.

Vyts Beliajus, based in Chicago, toured the country teaching a wide repertoire of dances picked up from various immigrant groups. His monthly magazine, Viltis, combined dance instruction and information [of sometimes dubious value] with “information and trivia from the private lives of folk dancers….engendering a feeling of community, continuity, and cohesion among people who were not regularly in touch or may never even have met.”

Michael Herman created the recreational folk dance movement on the East Coast. His multiple skills – musician, dance annotator, authoritative, clear teacher who emphasized fun, visionary who developed a permanent ‘home’ for folk dance, magazine publisher, and folk dance record producer – were unmatched anywhere. However, by skillfully creating and filling a market for ‘authentic’ folk dance records, he unwittingly helped transform the nature of folk dance.

Interestingly, San Francisco native Song Chang matured ‘outside’ the Scandinavian community from which he learned most ethnic dances, and ‘inside’ a network of artists, actors, & intellectuals. Was it this ‘artist-outsider’ status that influenced him to pursue folk dancing through perfecting and performing dances (doing dances), rather than as a venue for socialization (dancing)? Chang planted the seeds of many performing groups – soon to become a major genre within the recreational dance movement, especially in the West.

Chang’s pursuit of perfection also influenced another innovation. By the late 1930’s, especially in Chang’s California, an interest developed in a form of ‘top-down’ quality control – certifying dances ‘authentic’. This meant determining which was the ‘pure’ form of a dance, discouraging teachers from adding their own ‘enhancements’. It was an attempt to ensure a dancer could move from one group to another and expect to do the same dance in the same way at each place. An unintended consequence of this ‘homogenization’ of the dance experience was the shifting of personal focus from ‘dancing’ (self-expression) – to ‘doing dances’ (correct performance as determined by an authority) from being a creative individual dancer, an individual in a group of similar individuals, to being a conduit of a little-understood ethnic heritage; ‘active’ to ‘passive’ involvement – the return of Top Down dancing.

The Immigrant Period began with folk dance a specialty niche among social workers, educators, and phys ed teachers, accompanied by live music, and ended as a growing ‘craze’ with its own continent-wide network of clubs, summer camps, publications, record labels, and professional teachers.

COMMENTS:

Kate Reed wrote: “This is fantastic, Don. I am really thinking hard about how and why to participate in the folk dance scene. I especially appreciate your insight that recordings create a demand for fresh sounds, which people assume means fresh dances. I firmly believe people would enjoy doing the same dances to different music, if they understood that is the norm. People don’t understand that folk know a few dances and will embellish those when inspired. Our dance events are too heavy in teaching, imo, and too light in the experience of community connection through holding hands and following the energy of the music, while doing steps that everybody knows. I wonder how you, yourself, approach teaching and dancing, with your deep understanding. But realize that may need to be saved for a future real-life conversation! Perhaps at Lyrids next year.” Kate