*1st Generation dance. A dance that developed in a traditional way – not ‘taught’ by a teacher or choreographer, but ‘learned’ by observing and imitating others in your “village”, where the village’s few dances were the only dances anyone knew. It usually is ‘generic’ – the dance pattern is fairly simple and not tied to any particular piece of music. The dance phrase may or may not match any musical phrase, but the music’s rhythm must be suitable for performing the footwork. This dance may have many variations, but they’re performed at the whim or inspiration of the leader or (sometimes) any other dancer so long as it doesn’t interfere with the flow of neighboring dancers. For more, click here, here, and here.

Many thanks to Alex Marković, Serbian scholar extraordinaire, who helped me immensely in unrvalling the mysteries of what I thought would be the simple story of Vranjanka. His insights are quoted throughout.

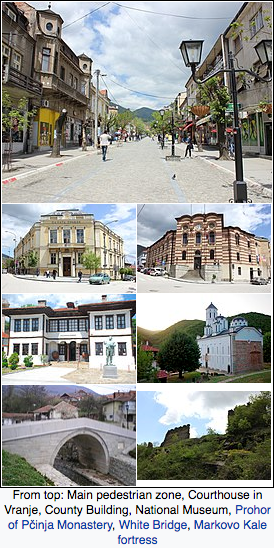

Vranje is the major town (pop. 60,000) of southern Serbia. The city name stems from the Old Serbian word vran (“black”). A Vranjanka (VRAN-yan-ka) is a female-gendered object (woman, flower, etc) from Vranje. Several songs, and several dances are associated with Vranje.

Though it was likely settled long before, the first written record of Vranje is from a Byzantine chronicle of 1093, which told of its seizure from the Byzantines by Serbians expanding from the north. The Byzantines quickly regained control, and tussled with the Serbs until 1207, when Serbian Grand Prince Stefan Nemanjić took charge definitively. Definitively, that is, as far as the Byzantines were concerned, for soon a new power from the East overwhelmed both the Byzantines and the Serbs. In 1455 the Ottoman Empire engulfed Vranje and the rest of Serbia, and Vranje remained under Ottoman control for 423 years, until the Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–1878). Most of the Muslim population of Vranje then fled to the Ottoman vilayet of Kosovo. The city entered the Principality of Serbia, with little more than 8,000 inhabitants at that time. The only Muslim population permitted to remain in the town after the war were Serbian speaking Muslim Romani (numbering 6,089 in 1910). Up until the end of the Balkan Wars, (1912-13) Vranje had a special position and role, as the transmission station of Serbian state political and cultural influence on Macedonia.

Serbian cultural scholar Alex Marković, in personal correspondence, wrote: “After WWII, with the creation of the second Yugoslavia under a Socialist regime, Vranje’s population underwent dramatic shifts. A Socialist emphasis on building industry and modernization meant factories opened in Vranje proper, drawing increasing numbers of people out of villages from all over the region and into the town pursuing work opportunities, cash wages, and ostensibly better living standards. Meanwhile, the older urban elites (particularly the wealthy merchant classes) had already been on the outflow, moving to bigger centers of power like Belgrade or large cities like Vienna and others in Central/Western Europe, following new lines of work, prospects for education, etc. This demographic shift meant that there was a gradual shift in dance culture as well- some things were held over, but others faded away.”

Vranje Songs

Alex Marković: “It seems that at least until WWII in town [Vranje – DB] a 5 measure pattern dance to slow(er) tunes in 7/8 meter was typical. Many local songs “fit the bill”, and even today local musicians typically play them in suites for dancers: Otvori Mi Belo Lenče, Šano Dušo (as you noted, actually composed outside and then popularized in Vranje afterward), but also others like Gajtano, mome mori; Puče Puska; Kaži Suto, kaži dušo; Kiša pade mori Cone; etc.”

However, most recreational folk dancers know of one, or at most two songs for the 5-measure dance pattern: Šano dušo, and/or Otvori mi belo Lenče.

Šano dušo

Best-known among recreational folk dancers is Šano dušo. For more on its composition, and for lyrics, click https://folkdancefootnotes.org/music/lyrics-english-translations/sano-duso-vranjanka-english-lyrics/ For sheet music, click https://folkdancefootnotes.org/music/sheet-music/sano-duso-vranjanka-sheet-music/

Ansambl Sumadija ¾ time. found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YWKIkefXBpI

Musician, Bakija Bakić Found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=53Hfiyw1dO0

Otvori mi, belo Lenče

Recreational folk dancers know the song by its abbreviated name, Belo Lenče, but most Serbs use the full title. There’s a fascinating story behind the song’s creation, which emerged in Vranje from “the folk” in the 1890’s. Find it, and also the lyrics here: https://folkdancefootnotes.org/ovtori-mi-belo-lence-vranjanka-the-story-the-song-the-english-lyrics-serbia/

As sung by Gordana Zahar Lazarević.

The album cover suggests a scene from the play Koštana. The album consists of songs sometimes used in the play.

Vranjanka Dances

Crum Version

Quoting the ©1998 Folk Dance Problem Solver: “Noted Balkan dance authority Dick Crum introduced this dance to the U. S. in 1955, calling it the original version from Vranje, as learned from natives. Many, many people have published music and words since then, but all descriptions trace back to Crum.”

Also in 1955, Crum published an extensive article in Viltis Magazine titled Some Background on the Kolo in the United States, which can be found here: https://folkdancefootnotes.org/dance/dance-information/ballroom-kolos-serbia-croatia/. In it, Crum describes “Ballroom Kolos” – dances that were not folk dances per se, but dances created from folk “material” that were arranged to suit the refined sensibilities of the urban middle and upper classes. In addition to the latest fashionable dances from Paris, Vienna, Budapest, etc, Serbians and Croatians of a patriotic bent in Belgrade, Novi Sad, Zagreb, etc incorporated these “Ballroom Kolos” into their social events. They wanted to emphasize their identification with the peasants in order to justify freeing the land from its Austro-Hungarian overlords.

“Among the other ballroom kolos familiar to us in America are Seljančica, Sarajevka, Vranjanka, Kokonješte, Žikino, Rumunsko and many others.…The fact that these ballroom kolos were widespread throughout Yugoslavia fifty years ago accounts for their being brought to America by the immigrants at that time. A count of the kolos now [ca. 1954 – DB] done in the U.S. will show that about 80% are of the old ballroom type. About the only “folk” kolos brought over were Malo, Veliko, Erdeljanka, Milica and the Drmesh.”

The “Crum version” has 5 measures

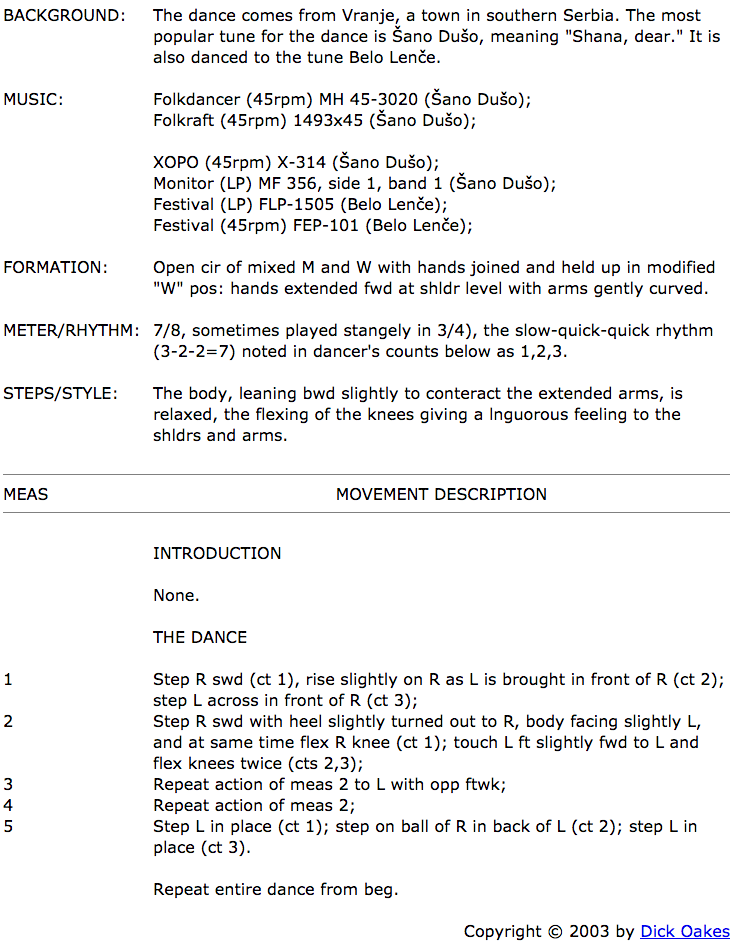

Below is reproduced the Crum 5-measure Vranjanka, from this site: http://www.folkdancenotes.com/dancenotes/Dick%20Oakes/Vranjanka.htm

Alex Marković again: “The Jankovic sisters were amazing researchers and recorded lots of valuable details, but there remains debate about the accuracy of their categorization of the Vranjanka and Teško melodies as 3/4 time, instead of the 7/8 that has long been the meter of dance tunes and songs that locals (in recorded and living memory) use to accompany these dances. Many scholars and local culture keepers believe that the 3/4 attribution is erroneous…but of course it may be that some tunes were authentically in 3/4 but they were stretched to 7/8 under the influence of other repertoires.”

Vranjanka among the Serbs

Alex Marković: “A 5 measure (bar) dance known as Vranjanka was part of the urban dance repertoire in Vranje from probably at least the late 19th century. It was documented by the Serbian dance researchers Danica and Ljubica Janković, during their visit to Vranje in the 1930s. They write that locals used the term Vranjanka for a slightly “lighter” aesthetic of movement for that 5 measure dance pattern, seemingly danced most often to specific songs from the urban repertoire (like Otvori Mi Belo Lenče). They noted though that the same 5 measure pattern was also danced in a more grounded/heavy aesthetic to a variety of tunes (including purely instrumental ones), and that locals called this “Teško” (i.e., “heavy dance,” which locals understand to mean slow and stately). So it seems that at least until WWII in town a 5 measure pattern dance to slow(er) tunes in 7/8 meter was typical.”

“This 5 measure pattern was more widespread even than just the environs of Vranje. In the Kosovo Pomoravlje area, in eastern Kosovo around the towns of Gnjilane/Gjilan and Novo Brdo, it was also the typical form used by locals for 7/8 tunes. This region is very close to Vranje and so this is probably not coincidence, but evidence of lots of cultural exchange.“

“Meanwhile, the older urban elites (particularly the wealthy merchant classes) had already been on the outflow, moving to bigger centers of power like Belgrade or large cities like Vienna and others in Central/Western Europe, following new lines of work, prospects for education, etc. This demographic shift meant that there was a gradual shift in dance culture as well- some things were held over, but others faded away….A 5 measure Vranjanka was “exported” further abroad with emigration of local urbanites to northern cities and towns in Serbia, and later even more with the spread of media and narratives of specific cultural traditions (“iconic” or “hallmark” practices) pegged to specific regions of the Kingdom of (and later, Socialist) Yugoslavia. In the early decades of this movement, Vranjanka became a “ballroom” type dance in those northern contexts- but my sense is that local aesthetics for tempo, musical accompaniment, and dance movement would have been quite different with time from local Vranje traditions. The Janković sisters indicate more delicate toe touches and some rocking of the hips for the lighter, Vranjanka form among local urbanites, but they also emphasize that the movements were subtle. Urbanites often emphasized that dignified restraint and subtlety were hallmarks of the upper class townsfolk, something they were proud of- to be contrasted with overly sharp or expansive movements, [not to mention] vigorous bouncing, which they saw as the realm of lower class and/or peasant culture…..There is great footage of local urban dancers performing a 5 measure Vranjanka, to a capella singing of Otvori Mi Belo Lenče, recorded in (or before) 1948. Given that these locals were still dancing a 5 measure pattern after WWII, I think it is fairly likely that at least some locals were still dancing it like that in the 1950s, and so that Dick Crum may have seen it on the ground there in Vranje.“

sung in a rhythm that seems (but not clearly so) closer to 3/4 than 7/8.

“It seems the 5 measure Vranjanka and Teško did just that, replaced gradually by a 3 measure pattern (like a lesnoto, in US folk dance parlance). I never saw a 5 measure pattern danced by anyone (old or young, Serb or Romani) over the course of my 17 months of fieldwork in Vranje. That said, it isn’t clear whether the 3 measure dance was always a “village” thing while the 5 measure was only “urban”; it seems that village populations also danced 5 measure patterns for at least some of that repertoire historically- villagers in eastern Kosovo, for instance, also danced the 5 measure pattern to slow 7/8 tunes. So it may just be that 3 measure patterns which existed alongside the 5 measure dances simply “won out” because they were simpler/more accessible to people, especially as people were congregating from all kinds of regional communities in Vranje and thus needed to create “common ground” in dance contexts.“

A wedding in Kočani, North Macedonia, 2007, people are dancing the T-7A Taproot Dance to the song Otvori mi belo Lenče, as seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N_-drYXPaBU

Svekrvino Kolo

“Today, most Vranje locals call the 3 measure dance that they perform to any and all of slow 7/8 tunes simply Teško (i.e., like the other dance name the Janković sisters noted, but also shifted from a 5 to a 3 measure dance form). Among other things, it is used for an important ritual dance led by the groom’s mother (called Svekrvino Kolo) at the beginning of three day weddings in the area- true for both Roma and Serbs, both in the town proper and in nearby villages“

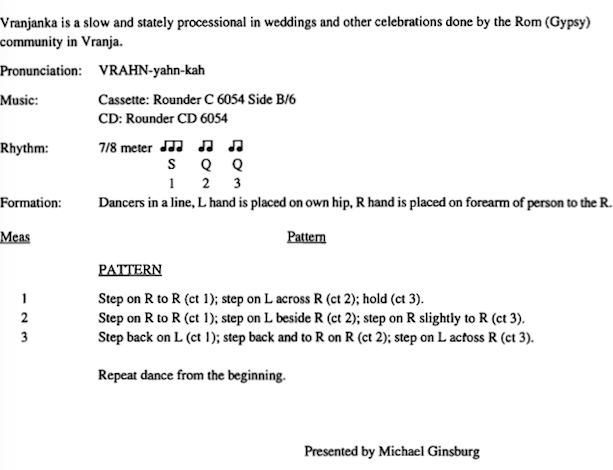

In 1994 Michael Ginsburg introduced a dance he called Vranjanka at Stockton. Looks a lot like Teško or Svekrvino Kolo, except for Ginsburg’s “escort” hold.

Performing groups

As if to prove Crum’s assertion that Vranjanka is not a folk dance per se, I can find no instances in Serbia of the choreography Crum said he saw in Yugoslavia in the 1950’s, except as demonstrated by students in a phys ed department.

Šano dušo from 2:35-3:28, Ovtori mi belo Lenče from 3:28-4:16

North American Serbians dance to Šano Dušo, but not using Crum’s 5-measure Vranjanka.

4-measure, 7/8 rhythm. Until 1:37.

SUMMARY:

It seems that the 5-measure dance noted in the 1930’s by the Janković sisters as being called Vranjanka or Teško was an urban dance from the Greater Vranje region, likely appearing after Vranje’s ‘liberation’ from the Ottomans in 1878, performed to whatever slower-tempo 7/8 music was available. After W.W.II, the ‘old guard’ of Vranje dispersed to larger cities within and beyond Yugoslavia, to be replaced by peasants moving in to work the new factories. Though the popular songs remained, the localized 5-measure dance Vranjanka (or Teško) was replaced by the more generic 3-measure dance – what I call the Taproot T-7A. Alex Marković says today the 3-measure dance is called Teško in the Vranje area. Googling Vranjanka or Teško, in either Latin or Cyrillic script, yields no current Serbian YouTubes (save the Phys Ed department, University of Novi Sad). However the dance often can be seen; the 5-measure version in performing groups (making it a perfect candidate for a 1st Generation dance), and the 3-measure version as a generic dance with many names or no name.