The text below is the complete article “Some Background on the Kolo in the United States” by Richard Crum from the October-November 1954 issue of Viltis magazine. This photo of Richard was on the cover.

In order to discuss the kolo situation in the United States today, we have to go back to the turn of the century and examine the dance background in Yugoslavia itself at the time when immigrants from that area began coming to our country. It’s difficult to get a good detailed picture of that period, because it wasn’t until 1934, through the pioneering efforts of the sisters Danica and Ljubica Jankovic, that any systematic attempt was made in Yugoslavia itself to collect, preserve and document its immense folk dance wealth. However we can piece together a sufficiently accurate picture to draw some general conclusions about Yugoslav dancing half a century ago. For our puropses it’s convienient to divide the subject into two aspects: ‘city’ dancing and ‘village’ dancing.

A long struggle to liberate itself from the Turks had built up within the Serbs an intense nationalism which appeared in their literature, music, and other facets of their culture. The way in which this national pride evidenced itself in the city dances is particularly interesting. City dancing masters began looking toward the folk dances for inspiration, and started composing ballroom dances in the native idiom. Along with the French quadrilles and other dances in vogue at urban balls, there began to appear ‘kolo’ dances, done in circles and lines, patterned after the kolos done in the villages. In many cases the dancing masters borrowed melodies and steps directly from the village dances, but these were usually a bit too brusque or crude, so they composed melodies and manufactured steps and figures, in an attempt to combine the folk element with the courtly style that was fashionable at the time.

These various composed kolos served the same purpose as Korobushka in Russia or the Beseda in Czechoslovakia. They were dances “in the manner” of native folk dances, but were intended for performance in the ballroom. Kolos of this kind numbered in the hundreds, and they came and went in popularity. They were taught in the fashionable dancing schools and spread throughout Yugoslavia.

Some were composed in honor of noble families or individuals, e. g. Jeftanovicevo*, Kurtovica, Kraljevo* oro, Natalijino**, etc.; others were dedicated to political parties: Radikalka*, Liberlno kolo, eyc; still others were given patriotic names: ***Serbkinja, Serbiaka, etc; a number were named for different sections of the city of Belgrade: čukaričko kokonješte, Savamalsko kolo, Dorčolka*, etc; certain professions had kolos dedicated to them: Oficirsko kolo, Profesorka, etc. [also Inženjerska kolo* – ‘engineer’ – see below, DB]

Biserka Bojerka

For much more about Biserka Bojerka, see: https://folkdancefootnotes.org/dance/a-real-folk-dance-what-is-it/2nd-generation-dances/biserka-bojerka-serbian-ballroom/

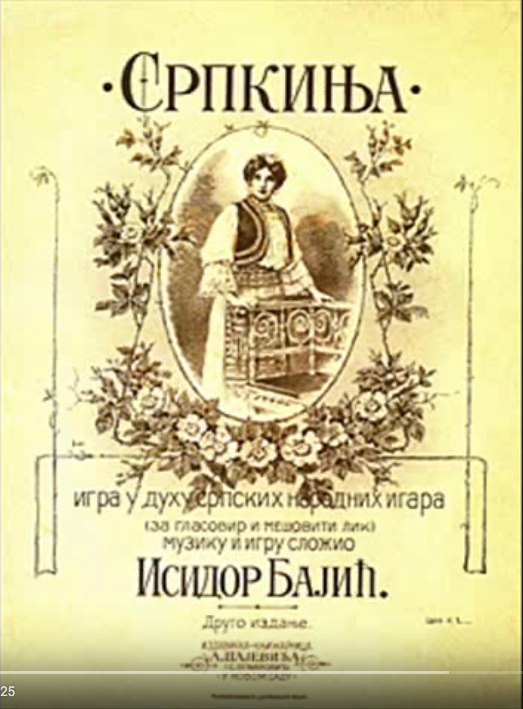

Kraljice Natalija (Natalijina kolo)

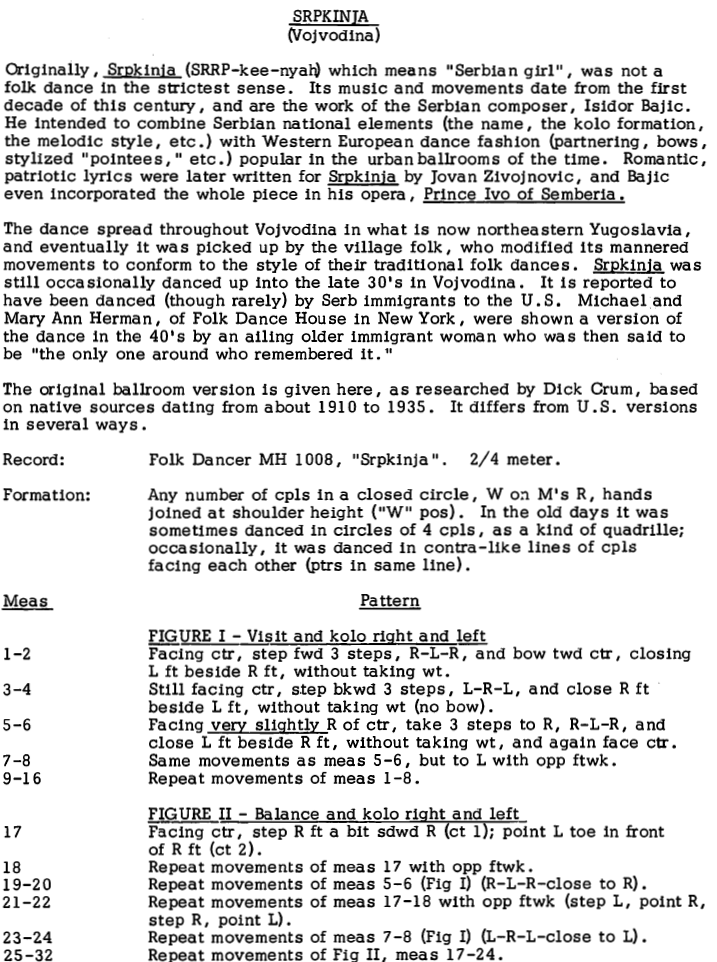

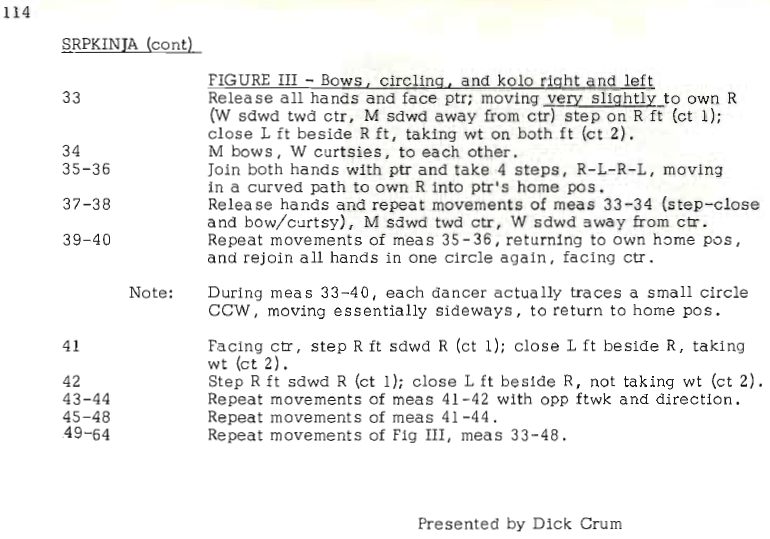

Srpkinja

For lyrics and English translation, see https://folkdancefootnotes.org/music/lyrics-english-translations/srpkinja-english-lyrics/

Nowadays, Srpkinja is popular in Serbia as a choir number, a performance by ballroom enthusiasts, and as a dance taught to children. DB

More ‘Ballroom’ Kolos

Among the other ballroom kolos familiar to us in America are Seljančica, Sarajevka, Vranjanka, Kokonješte, Žikino, Rumunsko and many others.

The fact that these ballroom kolos were widespread throughout Yugoslavia fifty years ago accounts for their being brought to America by the immigrants at that time. A count of the kolos now [ca. 1954 – DB] done in the U.S. will show that about 80% are of the old ballroom type. About the only “folk” kolos brought over were Malo, Veliko, Erdeljanka, Milica* and the Drmesh* (above).

To better understand why more village kolos were not brought over, we need only consider that any particular village dance is usually restricted to that village or its vicinity. Hence, it would have been difficult for people from different parts of Yugoslavia to get together and do each other’s dances. It was much easier to dance the more universal ballroom kolos which almost everyone knew. Of the new folk kolos that survived in the U.S., Malo, Veliko, Erdeljanka, and Milica were from the province of Voivodina, where the best tamburica players came from [DB note-see: https://folkdancefootnotes.org/music/tanbur-family-of-instruments/tamburica-tamburitsa-tamburizza-tambura-tamburica-orchestra/], and its probably through the tamburica players that the melodies and steps from these kolos became popular, after the immigrants were already in America. There is no other logical explanation for the fact that Croatians in this country, most of whom came from around Zagreb and Karlovac, are dancing kolos typical of Voivodina, far to the east.

The overwhelming majority of Yugoslav immigrants came from the northern area of the country (Croatia, Slovenia, and Voivodina), and of course brought with them cultural traits from those areas only (the tamburitza, “basic” step, etc.). However, the music and the dances of the rest of Yugoslavia never reached our shores. [This statement was soon to become obsolete, big time! – DB].

In other words, America received only a small, quite restricted sample of Yugoslav music and dance, consisting of about twenty ballroom kolos, four or five typical dances of Voivodina, and the music of the tamburitza instrument, which, while rich and beautiful, is only a fractional part of the real wealth of Yugoslav music.

It is a well-known fact that when people migrate from one area to another, the culture they carry with them retains certain elements from the original environment, but inevitably absorbs characteristics of the new surroundings. Most of the kolos brought to America eventually died out in Yugoslavia itself, while they lived on in this country among the second and third generation of Croatians and Serbs. However many changes took place in these dances, so that today when one observes them at Croatian and Serbian affairs, they are quite different from what they originally were.

Yugoslav-Americans tired of doing the kolos in the same way year after year – girls began dancing “basic step” with variations that looked tricky in high heels; boys improvised freer, broader figures similar to those of the jitterbug, and many steps were introduced, such as triple stamps in the middle of Seljančica, individual turns and calps in Zaplet, and complex scissor variations in Žikino.

American-born tamburitza players became interested in other types of music found among the nationality groups in the U.S. For example, tamburitza orchestras in America have a great love of Russian and Ukrainian music, because it is adaptable to the tamburitza instrument. Tamburaši may strike up “Hopak” during an intermission, someone makes up a kolo with crouches to go with the music, calls it Kozačko Kolo, and a new dance is on its way to becoming a standard favorite among the Serb and Croatian settlements throughout the country. American Yugoslavs have taken the Mexican “La Raspa” and created “King Kolo”, and recently they borrowed the Greek Syrto “Samiotissa”, dubbed it “Makedonka”, and even composed Serbian lyrics to go with it.

Dance leaders have appeared among the Croatian and Serbian colonies, and are trying hard to spread kolo among their own people. These leaders, often with great imagination, head kolo clubs in various cities, but unfortunately there is a lack of uniformity in the way they teach, so that Chicago kolo dancers are often unable to dance with those in Pittsburgh, who in turn differ from those further east, etc. A “Kolo Federation” has been organized in the East, but a feeling of competition has developed within it, prompting leaders to compose new kolos, to add many figures to originally simple dances, and to atttempt in other ways to outdo each other. Besides creating a confused situation for folk dancers who go to the “halls” to dance kolo authentically with the people, this sad element of competition has greatly jeapordized the success of what began as a healthy movement toward the preservation of Yugoslav dance in America.

There are very bright spots in the kolo picture, however, which offset some of the negative elements. First, there are a number of Croatian and Serbian colonies in the U.S. where the dances have been remarkably well preserved, notably New York and several smaller settlements in Pennsylvania. Secondly, the Duquesne University Tamburitzans, a Yugoslav music and dance group located in Pittsburgh, have made several trips to Yugoslavia itself to collect music and dances hitherto unknown in America, material which is being presented in concerts to the American Public. Thirdly, the recent popularity of kolos among non–Yugoslav folk dancers has stirred up a great deal of interest in kolo background, to the extent where there are probably more non-Yugoslavs dancing kolo than Yugoslavs themselves.