*S is for Song, *2 is for 2nd Generation dance

Chililin – the Song

A search for the meaning of the word “Chililin” in its native Quechua language has so far yielded nothing, and AI-generated translations aren’t helpful. Alan P. Knoerr wrote an extensive article about Chilili that was published in February 2022 in Folk Dance Scene magazine. “Using traditional farm implements, the plowing is done by oxen who often wear little bells hanging from their horns. The tinkling sound created is “chililín, chililín”.

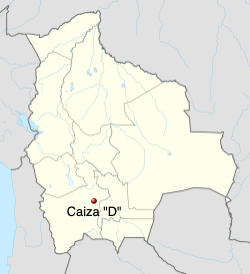

“CHILILIN IS A MUSIC ORIGINAL FROM CAIZA “D” THAT IS PLAYED DURING THE SOWING DAYS, ITS COMPOSITION DATES BACK MORE OR LESS 80 TO 100 YEARS, THEREFORE THE AUTHOR IS NOT KNOWN…” So says a caption to one version of this popular Bolivian song.

Original region of the song Potosi.

Lyrics as sung by Martita León in her Quechua language. An AI-generated translation into Spanish and English are suspect, but the Spanish-to-English translation seems closer to making sense.

Quechua - English

/Kunan p'unchayqua chililin chililin// //Today's chilly chilly//

//tarpurikamusun chililin chililin// //let's plant chilli chilli//

//ima yuguituwan chililin chililin// //what a yoke of chili chili//

//ichuu yuguituwan chililin chililin// //ichuu yuguitu and chili chili//

//ñapis yuntarinña chililin chililin// //already gathered chililin chililin//

//t'uru jallp'itaman chililin chililin// //chililin chililin to the ground//

//ima yuntitawan chililin chililin// //what a yuck is it chilling//

//sik'imiratawan chililin chililin// //chililin chililin with snow//

//tukuymi renanchis chililin chililin// //we all have to reign chililin chililin//

//mujuta apaspa chililin chililin// //carrying the seeds and chilling chillies//

//jallp'aman qonanpaj chililin chililin// //to give the ground chililin chililin//

//sumaj puqonampaj chililin chililin// //chililin chililin for nice fruit//

Spanish - English

hoy en este dia chililin chililin// //Today on this day//

nos sembraremos chililin chililin// //We will sow//

¿con que yuguito (yugo)? //With what yoke (yoke)?//

con yuguito de paja //With straw yoke//

a las tierras de barro //To the clay soils//

¿con que yuntita? //With what yuntita?//

con hormiguita //With ant//

¡vayamos todos! //Let's all go!//

llevando semilla //Carrying seed//

da la tierra //Gives the earth//

dando a la tierra //Giving to the earth//

para que produzca excelente //For it to produce excellently//

Other versions of the song Chililin

Another set of lyrics – this time of the KAiCHEÑOS, near Potosi. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WtO0FSZhOT8

Though sung in the original Qechua language, the closed captions included are in Spanish. Below is the Spanish captions with Google Translate converting it to English.

Hoy dia sembraremos chililin chililin Today we will sow chililin chililin

nuestra terreno chililin chililin repeat 2 lines our land chililin chililin repeat 2 lines

con que yunitita chililin chililin With what yoke (yoke)?

con hormiguitas chililin chililin repeat 2 lines With ant chililin chililin repeat 2 lines

con que aradito chililin chililin With which aradito chililin chililin

con aradito do palo chililin chililin repeat 2 lines With aradito do palo chililin chililin x2

con que yuguito chililin chililin With what yoke chililin chililin

con yuguito de paja chililin chililin repeat 2 lines With straw yoke chililin chililin x2 lines

hoy dia dos tomaremos chililin chililin Today two of us will drink chililin chililin

nuestra chichita chililin chililin repeat 2 lines Our chichita* chililin chililin x2 lines

hoy dia nos emborracharemos chililin chililin Today we will get drunk chililin chililin

con agua turbia chililin chililin repeat 2 lines With cloudy water chililin chililin x2 lines

*https://travelingjackie.com/how-the-ecuadorian-quechua-make-chicha-a-traditional-homemade-drink/

Other uses for the Chililin melody

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eqlBz8YubmY

QUECHUA

Paña makicha chililin chililin x2 Right hand x2

Lluqi makicha chililin chililin x2 Left hand x2

Paña chakicha chililin chililin x2 Right foot x2

Lluqi chakicha chililin chililin x2 Left foot x2

SPANISH

Manito derecha chililin chililin x2 Right hand x2

Manito izquierda chililin chililin x2 Left hand x2

Piecito derecho chililin chililin x2 Right foot x2

Piecito izquierdo chililin chililin x2 Left foot x2

AYMARA

Kupi amparalla chililin chililin x2 Right arm x2

Ch'iqa amparalla chililin chililin x2 Left arm x2

Kupi kayulla chililin chililin x2 Right foot x2

Ch'iqa kayulla chililin chililin x2 Left foot x2

Chililin, the Dance, is not Bolivian

Chililin, the dance, is not mentioned in lists of Bolivian dances, but appears to be related to C’alcheños, a dance which is mentioned, and which also comes from the Department of Potosi.

The dance of the C’kalcheños originates in the second section of the Nor Chichas province of the Department of Potosí and consists of giving thanks to the Andean deities for the fruits of the earth that allow the community to survive. With their baskets of fruit on their backs, they demonstrate the agricultural wealth of the area and with slow steps and sliding from one side to the other, they confirm the food security that Pachamama grants to those who are part of this Quechua region. The men wear the earth’s breeches, a wide, short shirt and a black shirt called “almilla” while the women wear the long, black dress also called “almilla” to whose edges abundant embroidery of beautiful colors is added and over it goes the “ajsu” that is adjusted to the waist with a sash called “chumpy”. It is another of the cultural expressions intended to highlight the role of nature in the life of the community and the gratitude for the gifts that come after long days of agricultural work. Source: https://mundopichinchafb.blogspot.com/p/blog-page_28.html

C’alcheños is a harvest dance. Chililin, a planting song, appears to use much the same footwork and formations, but differs in intent and implements. C’alcheños dancers carry baskets of harvested plants and thank the deities for their generosity, while Chililin dancers carry tools for plowing and tilling, and carry bags of seeds, helping the deities to produce their bounty. The basic step is the same for both dances R forward, L in place, R back, L in place in four even beats.

Alan P. Knoerr wrote an extensive article about Chilili that was published in February 2022 in Folk Dance Scene magazine. He wrote: In any case, “Chilili” is not the indigenous dance that authentically accompanies the indigenous song Chililín. Video evidence demonstrates that the indigenous dance which does so is found in more than one locality in the Potosí region of southwest Bolivia, is associated with more than one song…. Such dances do not

have a fixed choreography and encompass variations governed by the dancer, their community, and the circumstances in which they’re dancing.

What Chililín is, however, is a day of collaborative labor within a village where a family hosts a day of work with their neighbors and friends, providing food, drink, and childcare. It also includes a ceremony asking Pachamama (Mother Earth) to bless their efforts with a resulting bountiful corn harvest. Using traditional farm implements, the plowing is done by oxen who often wear little bells hanging from their horns. The tinkling sound created is “chililín, chililín”.

Chililin among Recreational Folk Dancers

Yves Moreau introduced this dance to North Americans at Stockton in 2007, writing, in a 2021 letter to Gigi Jensen “We learned the dance in Italy in 2006 from Silvio Lorenzato, a folk dance teacher from Vicenza in Northern, Italy. We understand that he had learned it from an immigrant Bolivian dance group based in Italy.” Although the song Chililin is undoubtably Bolivian, I can find no Bolivian YouTubes of footwork resembling the recreational dance Chilili. The basic step of Chilili – R,L,R,R touch, L,R,L,L touch, is not used in any Bolivian YouTubes of Chililin, or its parent dance, C’alcheños. Nor is the contra dance formation, except fleetingly, or the partner formation within the contra dance. Rather, the formations are mostly gender-based clusters. Hands don’t clap, as they are often carrying implements or miming sowing seeds. Chilili has no reference to sowing seeds, plowing ground or even springtime.

Gigi Jensen solves the Mystery of the Origin of the Dance Chililin

In 2021 Dale Adamson connected me to Gigi Jensen, a researcher in California concerned with the dearth of Latin-American-based folk dances, and especially with the misinformation connected with the few Latin-American we have. She was on a quest to uncover the the REAL origins of Chililin, the Dance as taught to recreational folk dancers worldwide, as spread by Sylvio Loranzato and Yves Moreau (who learned it from Sylvio). It took Gigi years to uncover the story, and finally it was published in the October 2023 edition of Let’s Dance! magazine, the publication of the Folk Dance Federation of California.

Here’s a summary if Gigi’s findings:

“Eddie Navio, a 60-something Ecuadorian man was a social worker with Detention Diversion Advocacy Project (DDAP) of the San Francisco Youth Correctional Administration. Its goal was to provide the sorts of services to kids that helped them grow into healthier lives, and to keep many from incarceration. Together, Eddie and the juveniles created a variety of dance choreographies, including the dance he called Chilili. Sadly, I was unable to find Mr. Navio. Given that he was in his sixties 30 years ago, odds are he’s passed away. Perhaps he returned to Ecuador. However, someone in the folk dance community did in fact meet him, or else the truth about Chilili would have been lost.

Getting the Chilili Word Out

Luc Vandenheede was living in Belgium and had a sister living in San Francisco, California. While visiting her in either spring 1996 or spring 1998, he saw a performance of Chilili by these young people in an open-air plaza in San Francisco. He talked with Mr. Navio, who shared the dance with Luc. Eddie gave Luc a cassette of the song, but it wasn’t very good quality. Luc found a shorter, cleaner version of the song on Unidisc by Los Gringos. When he returned to Belgium, he suggested the dance Chilili for the CD “Werelddance.”

Various teachers proceeded to teach Chilili, including Regula Leupold (Switzerland), who learned it from someone in the Netherlands, Adrian Gut (Switzerland), and Silvio Lorenzato (Italy). It was Silvio who taught the dance to Yves and France Moreau (Canada), who in turn taught it at Stockton Folk Dance Camp in 2007. It’s a fun little dance, to be sure, and it became very popular with folk dancers all over the world. In part, that popularity comes from it being one of very few Latin American dances that are available to international folk dancers.

Eddie Navio may, or may not, have known about the song’s connection to Bolivia. My personal take is that he liked the song and used it. Given that many of the serious juvenile offenders in the mid-1990s were from Latin American nations, it is possible that someone in that group was from the Andean region. Dale Adamson, who has listened to me for months talk about Chilili, said to me recently that she hopes I won’t let what I’ve learned get in the way of enjoying this fun dance. Now that I know that it was created to help young people envision a better life, you bet.“

And here’s full article as published in the October 2023 issue of Let’s Dance!.

SPEAKING OF DANCING

The Three Chililis

by Gigi Jenson

Chilili Changing Lives

The San Francisco Youth Correctional Administration was one of the worst in the country

since its inception in 1859. It was a spawning ground of lost lives. In 1993, San Francisco

created a new program: the Detention Diversion Advocacy Project (DDAP). Its goal was to

provide the sorts of services to kids that helped them grow into healthier lives, and to

kept many from incarceration. The program drew its staff from different ethnic

communities which provided a wide range of culturally specific interventions.

DDAP was so successful that it won numerous awards and recognition, including the San Francisco Delinquency Prevention Commission’s “Agency of the Year” award, and the “Diversity Award” from the Center on Human Development. It became a standard for the rest of the U.S. with other cities adopting similar programs.

One of the people who worked with these high-risk juveniles was a man identified as Eddie Navio, a 60-something Ecuadorian man who was a social worker. Together, Eddie and the juveniles created a variety of dance choreographies, including the dance he called Chilili. Sadly, I was unable to find Mr. Navio. Given that he was in his sixties 30 years ago, odds are he’s passed away. Perhaps he returned to Ecuador. However, someone in the folk

dance community did in fact meet him, or else the truth about Chilili would have been lost.

Getting the Chilili Word Out

Luc Vandenheede was living in Belgium and had a sister living in San Francisco, California. While visiting her in either spring 1996 or spring 1998, he saw a performance of Chilili by these young people in an open-air plaza in San Francisco. He talked with Mr. Navio, who shared the dance with Luc. Eddie gave Luc a cassette of the song, but it wasn’t very good quality. Luc found a shorter, cleaner version of the song on Unidisc by Los Gringos. When he returned to Belgium, he suggested the dance Chilili for the CD “Werelddance.”

Various teachers proceeded to teach Chilili, including Regula Leupold (Switzerland), who learned it from someone in the Netherlands, Adrian Gut (Switzerland), and Silvio Lorenzato (Italy). It was Silvio who taught the dance to Yves and France Moreau (Canada), who in turn taught it at Stockton Folk Dance Camp in 2007. It’s a fun little dance, to be sure, and it became very popular with folk dancers all over the world. In part, that popularity comes from it being one of very few Latin American dances that are available to international folk dancers.

And now for the Other One

Alan P. Knoerr wrote an extensive article about Chilili that was published in February 2022 in Folk Dance Scene magazine. He wrote: In any case, “Chilili” is not the indigenous dance that authentically accompanies the indigenous song Chililín. Video evidence demonstrates that the indigenous dance which does so is found in more than one locality in the Potosí region of southwest Bolivia, is associated with more than one song…. Such dances do not

have a fixed choreography and encompass variations governed by the dancer, their community, and the circumstances in which they’re dancing.

What Chililín is, however, is a day of collaborative labor within a village where a family hosts a day of work with their neighbors and friends, providing food, drink, and childcare. It also includes a ceremony asking Pachamama (Mother Earth) to bless their efforts with a resulting bountiful corn harvest. Using traditional farm implements, the plowing is done by oxen who often wear little bells hanging from their horns. The tinkling sound created is “chililín, chililín”.

If you want to know more, there is the Bolivian congressional document that outlines that “Declara Patrimonio Cultural e Inmaterial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolvia a la Danza del Chililin del Muncipio de Caiza D de la Provincia José María Linares del Departamento de Potosí.” Loosely translated, that means they’ve declared this dance to be an intangible national treasure. It’s written in Spanish and Quechu.

The Music is the Only Constant

The song that we dance to in the worldwide folk dance community is the same one that Eddie Navio and his teenage students used (albeit a shorter version), and that Luc Vandenheede shared with the Werelddance festival (the first song on the CD), and sometimes is the song used by the Bolivians for their mink’a (communinal day of corn planting). One name I found for that is “Chililín Campanita” (Tinkling Little Bells). It’s a pity that Los Gringos, the French group who recorded that for Unidisc, doesn’t get the credit they deserve. The next time you dance Chilili at your club, please mention them.

A few comments about Alan P. Knoerr’s article and where it falls short. He clearly did a great deal of well-done research. Adrian Gut did not create the dance. The dance was not

based on La Chacarera (which I teach), though similar figures are common throughout the

northern Argentina provinces of Santiago del Estero and Salta, as well as in Peru and Bolivia.

The version created in San Francisco was most likely not influenced by Spanish flamenco. Eddie Navio may, or may not, have known about the song’s connection to Bolivia. My personal take is that he liked the song and used it. Given that many of the serious juvenile offenders in the mid-1990s were from Latin American nations, it is possible

that someone in that group was from the Andean region. Dale Adamson, who has listened to me for months talk about Chilili, said to me recently that she hopes I won’t let what I’ve learned get in the way of enjoying this fun dance. Now that I know that it was created to help young people envision a better life, you bet.

It’s in my nature to ask, “Why?” Now I know