*S stands for Song, a category I apply to part of the repertoire of recreational folk dancers. Songs are just that – songs, or sometimes merely melodies, that are well-known in their country of origin, but aren’t necessarily associated with any particular dance. They may be traditional folk songs, or pop songs written in the folk style, or ‘pure’ pop creations that are dance-able. People will dance to them, but there is no culturally agreed upon ‘traditional’ dance that is particular to that song, just as we don’t associate any particular dance with “Blowin’ in the Wind” or “Lady Madonna”.

2* 2nd Generation Dance. A simple definition of a 2nd Generation folk dance (2ndG) is any dance that isn’t 1stG. More specifically it’s the context in which the dance was created – formal (2nd existence) rather than informal (1st Existence); conscious creation for a specific purpose rather than gradual evolution in a native context – that separates 1stG & 2ndG dances. For more detail on 1st & 2nd Existence situations, see A “Real” folk dance – what is it? 2ndG dances are specific – usually pegged to a specific song with a specific arrangement. The choreography often matches a particular recording and will only work with that recording. Everyone in the line does the same step at the same time. The dance may be a combination of the best bits from several similar dances. It may be the creation of a choreographer who liked a recording and wanted to have “authentic” footwork attached to it. In this particular case I classify Ya Abud as 2nd G, because, although it uses “authentic” debka steps and music, its choreography has a particular order designed to match a particular recording made for the dance.

I am indebted to HoraWiki “a treasury of Israeli folkdance information that anyone can edit!“, where much of the information below was taken. The particular article on Ya Abud can be found here. All information in this article in italics are taken directly from that article.

The Songs – An-Nadda Nadda & Jeeb il-Mijwiz Ya Abud

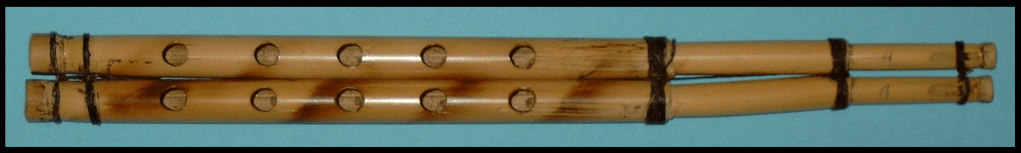

The music of Ya Abud is a combination of two different Lebanese tunes, both popularized by Jeanette Gergis al-Feghali, universally known as Sabah, a hugely popular Lebanese singer who lived from 1921 to 2014. The music of the first part of Ya Abud is the song “An-Nadda Nadda” (Arabic: عالندا الندا, “The Dew, The Dew”) and the music of parts two through seven is “Jeeb il-Mijwiz Ya Abud” (Arabic: جيب المجوز يا عبود, “Take the Mizwiz, O Abud!”; a mijwiz is a double flutelike instrument).

On Moshiko (Moshe Yitzak-Halevy) – Choreographer of Ya Abud

Excerpts in quotation marks are from the highly recommended book Seeing Jewish and Israeli Dance Edited by Judith Brin Ingber, Wayne Stare University Press. The book is the basis for my posting Israel and Early Israeli Dances, a good introduction to how European Jews molded Israel and Israeli dance in their own image.

Moshiko was born in Jaffa in 1932, from a Yemenite background. “I grew up in Jaffa before the War of Independence, when Jews and Arabs all mixed freely”

“Once, I remember, I was invited to participate in one of Histadrut’s folk dance courses. I knew the hora,

krakowiak, and polka from two years of kibbutz life, and I thought they were Israeli. I didn’t know they

were Polish and Rumanian dances, but after Inbal, [the first Yemenite dance troupe, Moshiko’s training ground, DB] I recognized they had no Jewish style. I began to wonder why we had to eat at a strange table, why we couldn’t try to taste of our own culture, to seek after something more real which we could be proud of.”

“When I was growing up no one said I had culture because I was Mizrahi*. Our embroidery, music, the intricate silver work in the jewelry and holy objects all around me weren’t recognized or prized at all.”

“For five years I worked with Arabs, Druze, and Circassians to help them develop their own culture. At

first they looked at me like I was crazy—how could a Jew come to tell them how to dance? I would go to

little towns and ask to watch dances, to learn them, and I would be told the dances were much too

difficult for me. But I knew from all my training that I could learn them. I would watch and then point

out parts of the dances that needed cleaning up or parts in the music that went against the movement. Often I’d argue with musicians and resolve the situation by saying that the musicians were playing for a group, they belonged to the group and everyone must work together. Finally, I would take the flute and show them what I wanted. Then each dancer would quietly come to me and ask if I were an Arab or a Jew. I would be trusted and could help the groups develop their ideas without losing the original material. I traveled all over the northern part of Israel, visiting different villages and learning dances.”

“In my own dances I don’t like to tell stories with the steps. I try to give an atmosphere and a flavor of

the Oriental style.” Observing him teach or lead is like watching a Pied Piper, for he uses no tape

recorders or microphones but accompanies himself with a variety of authentic flutes and pipes (hallilim),

interrupting his playing only to remind the dancers of a sequence or to correct someone’s stance or

execution in true dance teacher fashion. “As a result of dancing in this authentic way, I find that

dancers believe in what they are and to whom they belong. I can say that the biggest influence on my

work came from Sara Levi-Tanai’s searching and the way I worked in Inbal.”

*Mizrahi a term originally coined by Ashkenazi Jews to denote non-Ashkenazi Jews – “Easterners” the Jews who did not leave the Middle East, who did not mix with “civilized” European concepts – a nice term for “primitive”. Once in the minority in Israel, Mizrahi now form the majority.

The Dance

Ya Abud is an example of a debka, dabka, dabke – the generic dance of Arabs in the Levant (Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan) and beyond. For more on Dabke, click here.

Arabic: يا عبود (“O Abud!”, male name). Circle/line debka in seven parts by Moshiko HaLevy, 1974. Alternative title: Debka Abud.

Concerning debka in general and this dance in particular, Moshiko says: “Arabic debka is a kind of prayer. The Arabs, by stamping strong on the earth, are thanking the earth that’s supporting them. Most of the songs that accompany these dances are about love and women. Muslim leaders used to be against young boys dancing debka, feeling that dance was only for religious occasions, but after many years they realized that they cannot control the young boys and began to use those dances for all kinds of celebrations, like weddings, where it became popular.

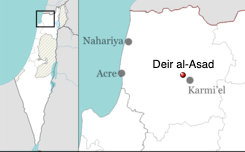

I made this dance when I was working with a Druze group in Ossafiya [now Isfiya-DB] in the Karmel mountain [Mount Carmel. DB]. I observed their material, and after having all the elements I made a choreography for their group. The elements are authentic Arabic which I learned from one of the elder dancers in their group (too long ago to remember his name—he was the instructor of the group until I came). I decided to make a choreography from the elements so they could perform them.” Interview with Moshiko, loosely translated, June 26 2020.

Choreographic Notes (see also videos below)

- Although the original instructions call for arms on shoulders, the right way to do the dance is with hands joined down in parts 1, 2, and 3; hands joined shoulder height in parts 4, 5, and 6; and hands joined circling to down in part 7.

- Part 5, bouncing on both feet, does not twist left and right or move forward. The bouncing is mostly in place, one long down and two quick up (international “mixed pickles” rhythm) with a slow progression around the circle LOD.

Other dances

A parody sing-along set of lyrics known as Fred Abud, written and often improvised by Ed Kaplan, was popular in the northeast US, especially Boston.